BKMT READING GUIDES

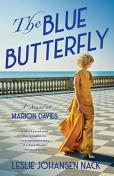

The Blue Butterfly: A Novel of Marion Davies

by Leslie Johansen Nack

Paperback : 352 pages

0 club reading this now

0 members have read this book

2023 IPPY Awards Silver Medalist in Historical Fiction

2023 IBPA Benjamin Franklin Awards, Gold Medal, Cover Design: Fiction

2023 IBPA Benjamin Franklin Awards Finalist in Fiction: Historical

2022 Readers’ Favorite Book Awards ...

Introduction

2023 IPPY Awards Gold Medalist in Audiobook - Fiction

2023 IPPY Awards Silver Medalist in Historical Fiction

2023 IBPA Benjamin Franklin Awards, Gold Medal, Cover Design: Fiction

2023 IBPA Benjamin Franklin Awards Finalist in Fiction: Historical

2022 Readers’ Favorite Book Awards Finalist in Fiction (Historical - Personage)

"A detailed, moving portrait of a complex woman in a complex life.”—Kirkus Reviews

“The Blue Butterfly is a vibrant period novel that reimagines the controversial love story of a classic film star.”—Foreword Reviews

“The book reads as if it really is Davies’ autobiography . . . . a timely reminder of what women would have been up against in Hollywood.”—Historical Novel Society

New York 1915, Marion Davies is a shy eighteen-year-old beauty dancing on the Broadway stage when she meets William Randolph Hearst and finds herself captivated by his riches, passion and desire to make her a movie star. Following a whirlwind courtship, she learns through trial and error to live as Hearst’s mistress when a divorce from his wife proves impossible. A baby girl is born in secret in 1919 and they agree to never acknowledge her publicly as their own. In a burgeoning Hollywood scene, she works hard making movies while living a lavish partying life that includes a secret love affair with Charlie Chaplin. In late 1937, at the height of the depression, Hearst wrestles with his debtors and failing health, when Marion loans him $1M when nobody else will. Together, they must confront the movie that threatens to invalidate all of Marion’s successes in the movie industry: Citizen Kane

Editorial Review

No Editorial Review Currently AvailableExcerpt

Chapter 1 New York, 1907 Mama named me Marion Cecilia Douras, and I was the baby in the family of five children. By the time I was ten, I had to fend for myself. Mostly, I like it that way. I was a tomboy, and being a troublemaker came easy to me. Mama wasn’t exactly neglectful. She just ran out of hugs By the time I was born—the fifth child in eleven years. She was tired and always preoccupied with my three older sisters and brother. Five-foot-two, with big bosoms and a stern voice, Rosemary Reilly Douras was discreet, mighty, and fierce, like a quiet thunderstorm. When she smiled, her eyebrows lifted, her mouth opened a little, and her face became soft and tender. When she smiled at me, which wasn’t often, my whole world lit up. Mama saw the bleak economic realities for women like us. Our opportunity to meet and marry wealthy, eligible men was In the theater, where the lines between the classes blurred. In the fantasy world filled with glitz and glamour, relationships between distinguished gentlemen and dancers were not openly acknowledged by high society, but they were prevalent. “It’s a way to get your foot in the door to a better life, ”Mama always said. Some might say she encouraged us to be gold diggers, but I say she helped us navigate the world the best she knew how. I hid in the shadows, sneaking in and out of rooms, watch- ing my two oldest sisters Reine and Ethel dress and do their hair before heading off to jobs in the theater. My third older sister, Rose, who was just two years older than me, stuttered like I did, which created an unspoken bond between us. Rose loved to boss me around, and we were in constant competition over everything. Of my three sisters, I was most like Ethel in personality. We were jokesters, kidders, and tricksters and strove to make people laugh, if not to outright shock them. We didn’t look alike at all. I had curly blonde hair and big blue eyes while Ethel had kinky brown hair and brown eyes—opposites on the outside, but twins on the inside. One time when I was eight, as a prank we hid in the pantry and sewed the meat of Reine’s roast beef sandwich together with a needle and thread. I held the sandwich and Ethel pushed the needle and thread up and down a few times so the meat wouldn’t pull apart when Reine bit into it. When we sat down to lunch, it was hard to keep a straight face as our dainty older sister, with her perfect chestnut hair and red lipstick, pulled and yanked the sandwich from her mouth. I snickered softly and the joke was up. Mama smacked my hand and gave Ethel a squinty- eyed scowl. Honestly, I hoped to grow up elegant like Reine, but funny like Ethel. Our only brother, Charlie, drowned before I could form too many memories of him. I was four and he was eleven when they found his body in the swamp behind our grandparents’ home in Florida. Mama never talked about what happened other than to say how it devastated Papa to lose his only son. In fact, Papa kind of slipped away from all of us after Charlie died, finding relief in drinking, gambling, and other women’s arms. Mama never said anything bad about Papa, but I saw her avoid eye contact with him. She didn’t have time to comfort him—she had four girls to raise in a society that favored wealthy men. In the early 1900s, women from all walks of life were uniting in their fight to gain the vote, silent movies were the rage, Theodore Roosevelt was president, the Ford Motor Company ruled the world of automobiles, and the only way for women to ascend their station in life was to marry up. Mama considered it her full- time job to get us girls ready for the Ziegfeld stage and as close as possible to all those rich gents who frequented the theater district. We all took singing and dancing lessons from the age of five. I went with Rose to tap class and excelled at backbends, walk overs, and the splits. Reine loved the Hesitation Waltz with its ballet-like features, while Ethel’s passion was the foxtrot and the fast dances. By the time Reine and Ethel were eighteen and sixteen years old, Mama knew she needed to get them closer to the work they were trained to do. This was how we came to live in the semi- posh neighborhood of Manhattan called Gramercy Park. I say we came to live, but really it was just Mama, Reine, and Ethel at first. Rose and I had to stay with Papa in Brooklyn during the week for elementary school and dance lessons. Compared to the Victorian house in Brooklyn, Gramercy Park felt like we’d taken a giant leap up in the world. The houses were brick and brownstone rowhouses, upscale and fashionable as were the people walking their dogs and pushing their baby carriages. I played basketball well enough to make the championship boys’ team in Brooklyn. But an athletic tomboy wasn’t valued at my house, so I vacillated between being a brash, outspoken romp at school in Brooklyn, and a prissy, elegant girl twirling and dancing in our Gramercy Park living room on the weekends, the kind of daughter I knew my mother wanted. One weekend in Gramercy Park, I joined the Second Street Gang, a pack of seven boys who played in the park across the street from our house. I placed my hair in a cap, put on some old trousers and a baggy shirt, and marched across the street, asking to join them. The leader, an older boy named Butch, said I could join if I could make it through that evening’s “fun.” Fearful of stuttering, I nodded and stared at the ground. “First, we gather old fruits and vegetables from behind the stores and put them in bags,” Butch said as he chewed a blade of grass. John, another gang member, leaned toward me with a scowl and said, “After that, you follow our lead. Got it?” I nodded again and followed the boys’ lead as we snuck to the back of the store to steal our ammunition. I grabbed rotten peaches, mushy plums, and stinky heads of brown lettuce. We ran to Prospect Park, where all the rich people lived. Butch ran up the stairs and rang the doorbell. We stood shoulder-to- shoulder at the bottom of the stairs, and when the door opened we fired our stash of produce at the butler until he slammed the door shut. Laughing, we ran to hide in the alley. We did this twice more. I wasn’t expecting it when Butch pushed me, so I stumbled back against the brick wall where I couldn’t hide my giant smile. “You’re in,” he said. “What’s your name?” “Marty,” I said in a low voice, happy I hadn’t stuttered and was part of the group. At the fourth house, we got rid of the rest of our produce— apples and carrots—but the police pulled up, surprising us. “Run!” Butch yelled and we scattered like cockroaches in the light, but the cops caught me, Butch, and one other boy. At the police station, after they hauled the boys down the hall, one of the cops asked me to take off my hat. I cowered in the bright lights, shaking as I pulled my newsboy cap into my lap, my blond hair tumbling to my shoulders. “Where do you live, little girl?” he asked. I gave him my address, and the policeman delivered me to Mama, who hauled me inside by my ear as she swatted my head. He cleared his throat, waiting for a chance to speak. “Ma’am, I thought you should know that one of the houses bombarded with rotten fruit was Mr. William Randolph Hearst’s house. His butler called to report the hooligans.” “Oh, I’m so sorry. I had no idea,” Mama said, closing the door in embarrassment. “You’re a hooligan now? ”Reine asked me as she sat on the couch, painting her nails. Reine was not somebody who’d join a gang, but I could tell she was pleased with me. “We’re so proud of you,” said Ethel, looking up from her magazine to wink at me. She had a tomboy streak too. “Stop encouraging her,” Mamma scolded. “We all need to keep a better eye on her.” Looking at me, she said, “Don’t you dare smile, little girl. I am sending you back to Brooklyn first thing in the morning.” I lowered my head in defeat as Reine and Ethels snickered quietly. “Don’t laugh,” I yelled at my sisters for Mama’s sake, but flashed a sly smile at them before marching upstairs. I missed dinner that night, but Ethel snuck me cookies and came to read and snuggle with me in bed. Watching the Second Street Gang play basketball from our living room window, I knew I’d never play with them again. Reine and Ethel’s work on the stage earned enough money to Pay the rent on our four-bedroom, two-bath house in Gramercy Park. They were the first to change our last name to Davies. They came up with the new last name when they saw a “Davies Real Estate” sign on the way home from the theater. Douras was too Irish of a name and was hindering them in getting jobs, while the last name of Davies was more European and acceptable. Mama reminded Reine and Ethel constantly about their real purpose for working in the theater—which was to marry a rich patron. I tried not to roll my eyes while she preached about avoiding the traps of romantic love. Money was more important than love, she told us. Reine, now twenty-one, was the first to make good on Mama’s wishes when she married a newly rich, forty-five-year-old theater director named George Lederer, and they immediately had two children, Charlie and Josephine. We all called Jose- phine “Pepi,” because she was. After a few years of marriage, they moved to Chicago where George turned his money into an absolute fortune with a chain of movie theaters. That’s when she invited all of us to move to Chicago to live with them in their palatial three-story, twenty-five-room mansion on the lake. I was thirteen and brought my tomboy toughness to Chicago, even though I was starting to get attention for my looks. The more attention I got, the easier it was to play the part—wearing fancy dresses, jewelry, and a little makeup. Ethel would compliment what she called my “angelic face and show-stopping eyes” whenever we were alone. Rose’s looks blossomed as well, but it seemed she veered away from the delicate features everyone admired. She felt slighted that I was getting all the attention and it was driving a wedge between us, but when we were getting along, we had plenty of fun. We stole the flowers from the vases in the entryway of George’s mansion and sold them on the street for candy and movie tickets. If we couldn’t raise enough money for the movies, we’d show up at one of his theaters and inform the cashier that we were the Lederer children and should be admitted for free. During our second year in Chicago, I almost lost my best sister Ethel, when she fell in love with a rich manufacturer. But after he asked his wife for a divorce and they fought, he had a heart attack and died. I know I shouldn’t have been happy, but I was. Ethel was mine, and I didn’t intend on sharing her with anybody. Reine had the freedom to work on stage, starring in some of the biggest plays in Chicago, because Mama watched Charlie and Pepi. One evening the whole family attended the premiere of her latest play. I got to watch her from the wings of the theater, standing just off stage with Mama, Ethel, and Rose. The split-second costume changes, and the men scurrying behind the curtains in a coordinated effort to raise the curtains and change the sets captured my complete attention. At the end of the play, after Reine sang in the grand finale but right before the curtain came down, I ran onto the stage to face the audience. They clapped and laughed at my shenanigans, when one of the stagehands tried to catch me with his stage hook and missed. It was comedy and I was hooked on it. I bowed and curtsied as I ran around the stage, evading him until I was sure the crowd loved me. The noise from the audience filled me up and made my insides glow. That feeling stayed with me and I looked forward to the day when I could be on stage in a production. Mama, of course, was less than pleased, and when they finally hauled me offstage, she grabbed me by the ear, forced me outside, and gave me a good spanking. Reine and Uncle George got divorced when I was sixteen, and we were all moved back to New York, where Ethel and Reine started their acting careers all over again. Even though George paid child support, twenty-seven-year-old Reine moved in with us, and we all helped with Charlie and Pepi.Discussion Questions

From the author:1. In many ways, Marion’s girlhood in Brooklyn was challenging. How do her early years prepare her to meet and fall in love with Hearst? What does life with Hearst offer her that she hasn’t encountered before? What are the risks?

2. Marion and Hearst sneak around for many years as Hearst is trying to secure a divorce from his wife. What seems to draw the two together? What do you think about the age difference between them? What are some of the strengths of their initial attraction and partnership? The challenges?

3. The William Randolph Hearst we meet in THE BLUE BUTTERFLY—through Marion’s eyes—is in many ways different from how we imagine him in his publishing empire. What do you see as his character strengths? Can you understand what Marion saw in him besides his money?

4. When Marion gives her child, Patricia, to her sister, Rose, to raise, do you think she made a wise choice? If not, what should she have done?

5. Hearst and Marion opt for California over New York. What was life like for Marion when she first arrived? How did she assert herself as a modern woman? How did Marion’s feelings about Hollywood differ from Hearst’s, and why?

6. Throughout THE BLUE BUTTERFLY, Marion is Hearst’s mistress but always wants to marry him. She is also a free agent when Hearst has family obligations. What do you think it is about Charlie Chaplin that draws Marion to him? How does this impact her relationship with Hearst? Her self-esteem? What are some of the modern themes Marion lives out?

7. How does the time and place—Hollywood in the 20s and 30s—affect Marion and Hearst’s relationship? What impact does the war, for instance, have on the choices of Hearst and Marion? Do you think Marion was born an alcoholic or became one because of the painful life she lives as the mistress in the shadow of Millicent?

8. What was the nature of the relationship between Hearst and Millicent in later years?

9. Marion is a very different person at the end of the novel than the girl who encounters Hearst on the Broadway stage. Do you think she had a happy life? How do you understand her trajectory and transformation? Are there any ways she remains essentially the same?

10. When Citizen Kane was released, how do you think it affected the legacy of Marion Davies?

11. After Hearst dies, what do you think about the way Millicent treated Hearst’s body and Marion in the final days of Hearst’s life? How did you feel when Marion was left out of Hearst’s funeral? Did you think Marion should have given back the stocks in The Hearst Corporation for $1?

Weblinks

| » |

Author's website

|

| » |

Publisher's book info

|

| » |

Follow the author on Instagram

|

| » |

Watch the book trailer

|

| » |

Presentation and Q&A at Mira Costa College LIFE Program

|

Book Club Recommendations

Recommended to book clubs by 0 of 0 members.

Book Club HQ to over 90,000+ book clubs and ready to welcome yours.

Get free weekly updates on top club picks, book giveaways, author events and more