BKMT READING GUIDES

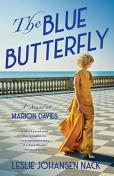

The Blue Butterfly: A Novel of Marion Davies

by Leslie Johansen Nack

Paperback : 352 pages

0 club reading this now

0 members have read this book

2023 IPPY Awards Silver Medalist in Historical Fiction

2023 IBPA Benjamin Franklin Awards, Gold Medal, Cover Design: Fiction

2023 IBPA Benjamin Franklin Awards Finalist in Fiction: Historical

2022 Readers’ Favorite Book Awards ...

Introduction

2023 IPPY Awards Gold Medalist in Audiobook - Fiction

2023 IPPY Awards Silver Medalist in Historical Fiction

2023 IBPA Benjamin Franklin Awards, Gold Medal, Cover Design: Fiction

2023 IBPA Benjamin Franklin Awards Finalist in Fiction: Historical

2022 Readers’ Favorite Book Awards Finalist in Fiction (Historical - Personage)

"A detailed, moving portrait of a complex woman in a complex life.”—Kirkus Reviews

“The Blue Butterfly is a vibrant period novel that reimagines the controversial love story of a classic film star.”—Foreword Reviews

“The book reads as if it really is Davies’ autobiography . . . . a timely reminder of what women would have been up against in Hollywood.”—Historical Novel Society

New York 1915, Marion Davies is a shy eighteen-year-old beauty dancing on the Broadway stage when she meets William Randolph Hearst and finds herself captivated by his riches, passion and desire to make her a movie star. Following a whirlwind courtship, she learns through trial and error to live as Hearst’s mistress when a divorce from his wife proves impossible. A baby girl is born in secret in 1919 and they agree to never acknowledge her publicly as their own. In a burgeoning Hollywood scene, she works hard making movies while living a lavish partying life that includes a secret love affair with Charlie Chaplin. In late 1937, at the height of the depression, Hearst wrestles with his debtors and failing health, when Marion loans him $1M when nobody else will. Together, they must confront the movie that threatens to invalidate all of Marion’s successes in the movie industry: Citizen Kane

Editorial Review

No Editorial Review Currently AvailableExcerpt

Chapter 1New York, 1907

Mama named me Marion Cecilia Douras, and I was the baby in

the family of five children. By the time I was ten, I had to fend for myself.

Mostly, I like it that way. I was a tomboy, and being

a troublemaker came easy to me.

Mama wasn’t exactly neglectful. She just ran out of hugs

By the time I was born—the fifth child in eleven years. She was

tired and always preoccupied with my three older sisters and

brother. Five-foot-two, with big bosoms and a stern voice, Rosemary

Reilly Douras was discreet, mighty, and fierce, like a quiet

thunderstorm. When she smiled, her eyebrows lifted, her mouth

opened a little, and her face became soft and tender. When she

smiled at me, which wasn’t often, my whole world lit up.

Mama saw the bleak economic realities for women like us.

Our opportunity to meet and marry wealthy, eligible men was

In the theater, where the lines between the classes blurred. In

the fantasy world filled with glitz and glamour, relationships

between distinguished gentlemen and dancers were not openly

acknowledged by high society, but they were prevalent. “It’s a

way to get your foot in the door to a better life, ”Mama always

said. Some might say she encouraged us to be gold diggers, but

I say she helped us navigate the world the best she knew how.

I hid in the shadows, sneaking in and out of rooms, watch-

ing my two oldest sisters Reine and Ethel dress and do their

hair before heading off to jobs in the theater. My third older

sister, Rose, who was just two years older than me, stuttered

like I did, which created an unspoken bond between us. Rose

loved to boss me around, and we were in constant competition

over everything.

Of my three sisters, I was most like Ethel in personality. We

were jokesters, kidders, and tricksters and strove to make people

laugh, if not to outright shock them. We didn’t look alike at all.

I had curly blonde hair and big blue eyes while Ethel had kinky

brown hair and brown eyes—opposites on the outside, but twins

on the inside.

One time when I was eight, as a prank we hid in the pantry

and sewed the meat of Reine’s roast beef sandwich together

with a needle and thread. I held the sandwich and Ethel pushed

the needle and thread up and down a few times so the meat

wouldn’t pull apart when Reine bit into it. When we sat down

to lunch, it was hard to keep a straight face as our dainty older

sister, with her perfect chestnut hair and red lipstick, pulled and

yanked the sandwich from her mouth. I snickered softly and the

joke was up. Mama smacked my hand and gave Ethel a squinty-

eyed scowl. Honestly, I hoped to grow up elegant like Reine, but

funny like Ethel.

Our only brother, Charlie, drowned before I could form too

many memories of him. I was four and he was eleven when they

found his body in the swamp behind our grandparents’ home in

Florida. Mama never talked about what happened other than to

say how it devastated Papa to lose his only son. In fact, Papa kind

of slipped away from all of us after Charlie died, finding relief in

drinking, gambling, and other women’s arms. Mama never said

anything bad about Papa, but I saw her avoid eye contact with

him. She didn’t have time to comfort him—she had four girls to

raise in a society that favored wealthy men.

In the early 1900s, women from all walks of life were uniting

in their fight to gain the vote, silent movies were the rage, Theodore

Roosevelt was president, the Ford Motor Company ruled the

world of automobiles, and the only way for women to ascend

their station in life was to marry up. Mama considered it her full-

time job to get us girls ready for the Ziegfeld stage and as close as

possible to all those rich gents who frequented the theater district.

We all took singing and dancing lessons from the age of five. I

went with Rose to tap class and excelled at backbends, walk overs,

and the splits. Reine loved the Hesitation Waltz with its ballet-like

features, while Ethel’s passion was the foxtrot and the fast dances.

By the time Reine and Ethel were eighteen and sixteen years

old, Mama knew she needed to get them closer to the work they

were trained to do. This was how we came to live in the semi-

posh neighborhood of Manhattan called Gramercy Park. I say

we came to live, but really it was just Mama, Reine, and Ethel

at first. Rose and I had to stay with Papa in Brooklyn during the

week for elementary school and dance lessons.

Compared to the Victorian house in Brooklyn, Gramercy

Park felt like we’d taken a giant leap up in the world. The houses

were brick and brownstone rowhouses, upscale and fashionable

as were the people walking their dogs and pushing their baby

carriages.

I played basketball well enough to make the championship

boys’ team in Brooklyn. But an athletic tomboy wasn’t valued

at my house, so I vacillated between being a brash, outspoken

romp at school in Brooklyn, and a prissy, elegant girl twirling

and dancing in our Gramercy Park living room on the weekends,

the kind of daughter I knew my mother wanted.

One weekend in Gramercy Park, I joined the Second Street

Gang, a pack of seven boys who played in the park across the

street from our house. I placed my hair in a cap, put on some old

trousers and a baggy shirt, and marched across the street, asking

to join them. The leader, an older boy named Butch, said I could

join if I could make it through that evening’s “fun.”

Fearful of stuttering, I nodded and stared at the ground.

“First, we gather old fruits and vegetables from behind the

stores and put them in bags,” Butch said as he chewed a blade

of grass.

John, another gang member, leaned toward me with a scowl

and said, “After that, you follow our lead. Got it?”

I nodded again and followed the boys’ lead as we snuck to

the back of the store to steal our ammunition. I grabbed rotten

peaches, mushy plums, and stinky heads of brown lettuce. We

ran to Prospect Park, where all the rich people lived. Butch

ran up the stairs and rang the doorbell. We stood shoulder-to-

shoulder at the bottom of the stairs, and when the door opened

we fired our stash of produce at the butler until he slammed

the door shut. Laughing, we ran to hide in the alley. We did

this twice more. I wasn’t expecting it when Butch pushed me,

so I stumbled back against the brick wall where I couldn’t hide

my giant smile.

“You’re in,” he said. “What’s your name?”

“Marty,” I said in a low voice, happy I hadn’t stuttered and

was part of the group.

At the fourth house, we got rid of the rest of our produce—

apples and carrots—but the police pulled up, surprising us.

“Run!” Butch yelled and we scattered like cockroaches in the

light, but the cops caught me, Butch, and one other boy.

At the police station, after they hauled the boys down the

hall, one of the cops asked me to take off my hat. I cowered in

the bright lights, shaking as I pulled my newsboy cap into my

lap, my blond hair tumbling to my shoulders.

“Where do you live, little girl?” he asked.

I gave him my address, and the policeman delivered me to

Mama, who hauled me inside by my ear as she swatted my head.

He cleared his throat, waiting for a chance to speak. “Ma’am,

I thought you should know that one of the houses bombarded

with rotten fruit was Mr. William Randolph Hearst’s house. His

butler called to report the hooligans.”

“Oh, I’m so sorry. I had no idea,” Mama said, closing the

door in embarrassment.

“You’re a hooligan now? ”Reine asked me as she sat on the

couch, painting her nails. Reine was not somebody who’d join

a gang, but I could tell she was pleased with me.

“We’re so proud of you,” said Ethel, looking up from her

magazine to wink at me. She had a tomboy streak too.

“Stop encouraging her,” Mamma scolded. “We all need to

keep a better eye on her.”

Looking at me, she said, “Don’t you dare smile, little girl.

I am sending you back to Brooklyn first thing in the morning.”

I lowered my head in defeat as Reine and Ethels snickered

quietly. “Don’t laugh,” I yelled at my sisters for Mama’s sake,

but flashed a sly smile at them before marching upstairs. I missed

dinner that night, but Ethel snuck me cookies and came to read

and snuggle with me in bed. Watching the Second Street Gang

play basketball from our living room window, I knew I’d never play

with them again.

Reine and Ethel’s work on the stage earned enough money to

Pay the rent on our four-bedroom, two-bath house in Gramercy

Park. They were the first to change our last name to Davies. They

came up with the new last name when they saw a “Davies Real

Estate” sign on the way home from the theater. Douras was too

Irish of a name and was hindering them in getting jobs, while the

last name of Davies was more European and acceptable.

Mama reminded Reine and Ethel constantly about their real

purpose for working in the theater—which was to marry a

rich patron. I tried not to roll my eyes while she preached about

avoiding the traps of romantic love. Money was more important

than love, she told us.

Reine, now twenty-one, was the first to make good on

Mama’s wishes when she married a newly rich, forty-five-year-old

theater director named George Lederer, and they immediately

had two children, Charlie and Josephine. We all called Jose-

phine “Pepi,” because she was. After a few years of marriage,

they moved to Chicago where George turned his money into an

absolute fortune with a chain of movie theaters. That’s when she

invited all of us to move to Chicago to live with them in their

palatial three-story, twenty-five-room mansion on the lake.

I was thirteen and brought my tomboy toughness to Chicago,

even though I was starting to get attention for my looks. The more

attention I got, the easier it was to play the part—wearing fancy

dresses, jewelry, and a little makeup. Ethel would compliment

what she called my “angelic face and show-stopping eyes”

whenever we were alone.

Rose’s looks blossomed as well, but it seemed she veered

away from the delicate features everyone admired. She felt

slighted that I was getting all the attention and it was driving

a wedge between us, but when we were getting along, we had

plenty of fun. We stole the flowers from the vases in the entryway

of George’s mansion and sold them on the street for candy and

movie tickets. If we couldn’t raise enough money for the movies,

we’d show up at one of his theaters and inform the cashier that

we were the Lederer children and should be admitted for free.

During our second year in Chicago, I almost lost my best sister

Ethel, when she fell in love with a rich manufacturer. But after he

asked his wife for a divorce and they fought, he had a heart attack

and died. I know I shouldn’t have been happy, but I was. Ethel was

mine, and I didn’t intend on sharing her with anybody.

Reine had the freedom to work on stage, starring in some of

the biggest plays in Chicago, because Mama watched Charlie

and Pepi. One evening the whole family attended the premiere

of her latest play. I got to watch her from the wings of the

theater, standing just off stage with Mama, Ethel, and Rose. The

split-second costume changes, and the men scurrying behind

the curtains in a coordinated effort to raise the curtains and

change the sets captured my complete attention. At the end

of the play, after Reine sang in the grand finale but right before the

curtain came down, I ran onto the stage to face the audience.

They clapped and laughed at my shenanigans, when one of the

stagehands tried to catch me with his stage hook and missed. It

was comedy and I was hooked on it. I bowed and curtsied as I ran

around the stage, evading him until I was sure the crowd loved me.

The noise from the audience filled me up and made my

insides glow. That feeling stayed with me and I looked forward

to the day when I could be on stage in a production. Mama, of

course, was less than pleased, and when they finally hauled me

offstage, she grabbed me by the ear, forced me outside, and

gave me a good spanking.

Reine and Uncle George got divorced when I was sixteen, and

we were all moved back to New York, where Ethel and Reine

started their acting careers all over again. Even though George

paid child support, twenty-seven-year-old Reine moved in with

us, and we all helped with Charlie and Pepi.

...

Discussion Questions

From the author:1. In many ways, Marion’s girlhood in Brooklyn was challenging. How do her early years prepare her to meet and fall in love with Hearst? What does life with Hearst offer her that she hasn’t encountered before? What are the risks?

2. Marion and Hearst sneak around for many years as Hearst is trying to secure a divorce from his wife. What seems to draw the two together? What do you think about the age difference between them? What are some of the strengths of their initial attraction and partnership? The challenges?

3. The William Randolph Hearst we meet in THE BLUE BUTTERFLY—through Marion’s eyes—is in many ways different from how we imagine him in his publishing empire. What do you see as his character strengths? Can you understand what Marion saw in him besides his money?

4. When Marion gives her child, Patricia, to her sister, Rose, to raise, do you think she made a wise choice? If not, what should she have done?

5. Hearst and Marion opt for California over New York. What was life like for Marion when she first arrived? How did she assert herself as a modern woman? How did Marion’s feelings about Hollywood differ from Hearst’s, and why?

6. Throughout THE BLUE BUTTERFLY, Marion is Hearst’s mistress but always wants to marry him. She is also a free agent when Hearst has family obligations. What do you think it is about Charlie Chaplin that draws Marion to him? How does this impact her relationship with Hearst? Her self-esteem? What are some of the modern themes Marion lives out?

7. How does the time and place—Hollywood in the 20s and 30s—affect Marion and Hearst’s relationship? What impact does the war, for instance, have on the choices of Hearst and Marion? Do you think Marion was born an alcoholic or became one because of the painful life she lives as the mistress in the shadow of Millicent?

8. What was the nature of the relationship between Hearst and Millicent in later years?

9. Marion is a very different person at the end of the novel than the girl who encounters Hearst on the Broadway stage. Do you think she had a happy life? How do you understand her trajectory and transformation? Are there any ways she remains essentially the same?

10. When Citizen Kane was released, how do you think it affected the legacy of Marion Davies?

11. After Hearst dies, what do you think about the way Millicent treated Hearst’s body and Marion in the final days of Hearst’s life? How did you feel when Marion was left out of Hearst’s funeral? Did you think Marion should have given back the stocks in The Hearst Corporation for $1?

Weblinks

| » |

Author's website

|

| » |

Publisher's book info

|

| » |

Follow the author on Instagram

|

| » |

Watch the book trailer

|

| » |

Presentation and Q&A at Mira Costa College LIFE Program

|

Book Club Recommendations

Recommended to book clubs by 0 of 0 members.

Book Club HQ to over 90,000+ book clubs and ready to welcome yours.

Get free weekly updates on top club picks, book giveaways, author events and more