BKMT READING GUIDES

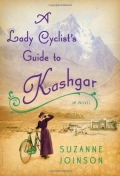

A Lady Cyclist's Guide to Kashgar: A Novel

by Suzanne Joinson

Hardcover : 384 pages

3 clubs reading this now

1 member has read this book

Introduction

It is 1923. Evangeline (Eva) English and her sister Lizzie are missionaries heading for the ancient Silk Road city of Kashgar. Though Lizzie is on fire with her religious calling, Eva's motives are not quite as noble, but with her green bicycle and a commission from a publisher to write A Lady Cyclist's Guide to Kashgar, she is ready for adventure.

In present day London, a young woman, Frieda, returns from a long trip abroad to find a man sleeping outside her front door. She gives him a blanket and a pillow, and in the morning finds the bedding neatly folded and an exquisite drawing of a bird with a long feathery tail, some delicate Arabic writing, and a boat made out of a flock of seagulls on her wall. Tayeb, in flight from his Yemeni homeland, befriends Frieda and, when she learns she has inherited the contents of an apartment belonging to a dead woman she has never heard of, they embark on an unexpected journey together.

A Lady Cyclist's Guide to Kashgar

explores the fault lines that appear when traditions from different parts of an increasingly globalized world crash into one other. Beautifully written, and peopled by a cast of unforgettable characters, the novel interweaves the stories of Frieda and Eva, gradually revealing the links between them and the ways in which they each challenge and negotiate the restrictions of their societies as they make their hard-won way toward home. A Lady Cyclist's Guide to Kashgar marks the debut of a wonderfully talented new writer.Discussion Questions

1. Missionaries play a major role in the book, and female missionaries lived fascinating lives at a time when women weren’t doing much independent travel. What did you think of the women’s mission and lifestyle?2. Did you expect the character of Tayeb to be as gentle and sympathetic as he is? Did anything about his introduction lead you to believe otherwise?

3. As the storyline alternates between Evangeline and Frieda, did you feel them moving closer together across the years?

Notes From the Author to the Bookclub

Suzanne Joinson Barnes and Noble Essay — 12 May 2012 Me and My Bicycle Writing a novel takes a long time: manuscript and life twist around each other like a wisteria trunk on an ancient arbor. I circled the idea of writing A Lady Cyclist's Guide to Kashgar while doing a creative writing MA at Goldsmiths, University of London. English missionaries, I thought, deserts, China, camels...You have to be kidding. Halfway through the course I got married and spent my honeymoon driving around New Mexico, Texas, and Arizona. We stopped off at a curious-looking bookshop/art gallery in a place called Van Horn. It was a very meta-experience. This was the small town of all the cowboy films and American road movies I'd ever seen. I was after a copy of Edward Abbey's Desert Solitaire and the bookshop owner-who introduced himself as Ran Horn of Van Horn-went out back to get me his own personal copy to sell. I read it as we covered miles of Texan desert and it was during this magical, slightly unreal journey that I came across this quote: "A man on foot, on horseback or on a bicycle will see more, feel more, enjoy more in one mile than the motorized tourists can in a hundred miles." Although it was quite a leap from reading Abbey in Texas to missionaries in China, something connected and the bicycle was the link. A voice in my head said: "Go for it." This was my first taste of what I now (pretentiously) call the Apophenia Zone, or an attack of the apophenics. This is the part of the novel-writing process in which the whole world-everything read, seen, spoken, thought, wanted, or wished-is connected and meaningful to the book. Messages and stories come from all directions, each detail insisting on its relevance and inclusion. During this time I found a manual from 1896 called Bicycling for Ladies. I remembered the 1920s and '30s travel writing I'd been obsessed with a few years earlier. Each drawing in my sketchbook, each pigeon flying past the window, and each turn of my own pedal as I cycled through London dripped its essence into the novel. Eighteen months later: I am sitting in the Special Collection basement of the School of Oriental and African Studies in London and I am eight-and-a-half months pregnant. In front of me are letters, diaries, and journals. The manic apophenics are replaced with calm historical research and I am trying to answer a question: Why did women missionaries choose to travel so far from home? It is rich material. After World War I, with so many men gone, the viable alternatives to marriage for single women were few. There was a surge in applications to the missions and when new recruits arrived in Peking or Sinkiang they were confronted with huge city walls built to keep desert storms out; with houses that appeared to be inward-looking, with no external windows; with closed gardens and unimaginably confusing souqs and bazaars. In the midst of this exotic strangeness the missionaries shed European clothes and with them the modes of behaviours and restrictive social codes of home. They carved out radical, even revolutionary, lives. Down in the basement, though, I am still trying to find a trapdoor in that will open up my story. I am looking for a pathway that will lead me towards the necessary architecture of my own novel which grows ever bigger. It is weighed down by too many ghost-words. With a kick in the stomach and a rush of heartburn, the idea comes to me: a baby, into one of these houses of childless, husbandless women, and the overwhelming emotions that come with the responsibility of doing everything in one's power to not lose such a creature. When my son was one year old I knew there was nothing for it, I had to visit Kashgar. On the plane I wrote and rewrote a passage in my notebook, wrestling with a knotty plot problem. I needed my character to escape from a city with a baby in a bicycle basket, but was this feasible? I was worried. I was a lot more worried, however, when I arrived in Kashgar. In nearby Urumqi a riot was occurring. Muslim Uyghurs were uprising against Chinese authorities, and the tensions had spread to Kashgar. The entire region was in lock-down: no internet, no international calls out, and soldiers everywhere. When I did speak to my husband (he could call in) the line clicked: we were being listened to. Alone in that hotel room I unwillingly became my character. She lived in the 1920s, sure, but I knew how it felt to be stranded in an ancient city, unable to comprehend the complex wars that were occurring outside. To calm myself I read a book I'd brought with me and was relieved to discover that when Lawrence Durrell and his wife Nancy fled Greece (in 1941, fleeing the Nazis) they carried their three month old daughter Pinkie in a pannier basket "like a loaf of bread." That, at least, was possible. There was a knock on the door; it was a serious looking Chinese official. He informed me that foreign journalists had been requested to leave. I told him that I was not a journalist. He peered into my room where an open laptop, a notebook, and a camera were splayed across the bed. On the long flight home I thought of Iris Murdoch's "bicycles are the most civilized conveyance known to man." For months afterwards I circled the city, with notebooks in my basket, until eventually the sense of freedom, flight, running away, and migration settled into my words and I found my way into the story.Book Club Recommendations

Recommended to book clubs by 0 of 0 members.

Book Club HQ to over 88,000+ book clubs and ready to welcome yours.

Get free weekly updates on top club picks, book giveaways, author events and more