BKMT READING GUIDES

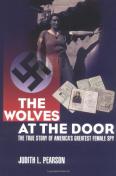

The Wolves at the Door: The True Story of America's Greatest Female Spy

by Judith L. Pearson

Hardcover : 288 pages

2 clubs reading this now

0 members have read this book

Introduction

Perhaps more than any other single factor of World War II, the Nazi persecution and extermination of Jews, gypsies and other groups is seen as the war's greatest tragedy. The number of deaths is staggering: six million Jews, four million Soviet POWs, three million non-Jewish Polish civilians, one million Serbs, more than 100,000 German and Polish mentally ill or physically retarded, and hundreds of thousands of gypsies and slave laborers from western Europe and the Balkans. These figures, forever etched in human history, cause us to struggle for understanding: how and why could such massive deaths have occurred? Stories of the incredible courage exemplified by those who struggled against Hitler's Third Reich are told and retold. I believe that such stories give us hope to overcome the adversaries we encounter in our everyday lives. Certainly, we think to ourselves, if common men and women were able to rise above and conquer those fiendish barbarians, we should be able to master the challenges facing us. When reduced to its most simple theme, Wolves at the Door exudes that kind of hope. It is a book about a woman of privilege and means, living with an enormous handicap, who exchanges her life of comfort for one of risk, joining in the fight to preserve mankind. Interspersed with Hall's story will be pertinent details of the war in Europe, Allied strategies and the homefront. Virginia Hall was born in 1906 into a milieu of wealth and privilege in Baltimore, MD. Hall left her comfortable Baltimore roots in1931 to follow her dream of becoming a Foreign Service Officer. She began her career as a clerk at the American embassy in Poland. The next stop was the American consulate in Izmir, Turkey, where Virginia's life took an unexpected turn: she accidentally shot herself in the left foot on a hunting expedition. Gangrene set in and Hall lost her left leg from the knee down. Despite her handicap, she had hoped to continue her State Department career as a Foreign Service Officer, but left in disgust in 1939, when her career was roadblocked. According to a bizarre regulation for Foreign Service employees, "any amputation of a portion of a limb … is cause for rejection in the career field." Hall remained in Europe and was in Paris when Hitler's war machine rolled into Poland in 1939. When France fell to the Nazis in 1940, she left for London. Hall was working as a code clerk at the American embassy when she was recruited by the British paramilitary service known as the Special Operations Executive (SOE). Their mission was to undertake sabotage and subversion, and to form secret military forces in German occupied Europe. The SOE was to initially act as an intelligence gathering operation, but would eventually, in the words of Winston Churchill, "set Europe ablaze." In the SOE Hall learned skills that her wealthy Baltimore contemporaries could not have conceived of. She became an expert in weaponry, communications, resistance activities and security. Because of her command of the French language, her first assignment was to establish resistance networks in unoccupied France, the first female SOE agent to do so. When the United States entered the war in 1941, Hall's job became much more perilous. Her country was now a Nazi enemy and she had to be constantly vigilant to avoid Gestapo officers. Captured spies were imprisoned, beaten and tortured. Some were then mercifully executed while others faced slow, painful deaths. The Nazis were unlike any foe previously encountered by Great Britain or the United States. They fought with little regard for the rules of gentlemanly warfare. Their fundamental belief, blut und boden (blood and soil) was that a healthy nation was one of a people with common blood, living on its own soil. This belief excluded many groups, including the six million Jews living in Europe. Hitler's Endlösung followed. It was the Final Solution: the extermination of all Jews. Against such an ominous backdrop, Hall managed to locate drop zones for the money and weapons so badly needed by the French Resistance. Under the very noses of the Gestapo, she helped escaped POWs and downed Allied airmen flee to England. And despite the vast numbers of Nazi sympathizers throughout France (many of whom were paid by the Germans for information or the delivery of spies), Hall secured safe houses for agents in need. It is difficult to determine which is most remarkable: the fact that Virginia Hall achieved all of this in spite of her handicap; or her motivation for risking her life in such a fashion. This motivation was not borne out of family obligation - the Halls were not Jewish nor did they have relations living under Nazi brutality. Neither was she filling empty hours waiting for a husband or lover to return from the war. Had she so chosen, Hall could have remained firmly ensconced in Baltimore society, courted by wealthy young men, literally a world away from the peril and misery of war torn Europe. It becomes apparent that Hall's extraordinarily courageous work with the French underground came from a selfless and extremely high standard of personal conduct. Her sense of right was challenged by the Nazi onslaught and it evoked a commitment to help defeat the Axis power. The more she saw, the more revolted she became, determined in her work against them. The Nazi intelligence organization was also adept, and a profile soon developed of a treacherous individual suspected of espionage. This spy's most noticeable trait was a limp and wanted posters soon appeared throughout France offering a reward for the capture of "the woman with a limp. She is the most dangerous of all Allied spies and we must find and destroy her." By winter of 1942 Hall had no choice but to flee France via the only route possible: a hike on foot through the frozen Pyrénées Mountains into neutral Spain. The escape was arduous and Hall's artificial leg (which she had nicknamed "Cuthbert") became very painful. In a radio message to London during the journey, she mentioned that Cuthbert was giving her trouble. Forgetting her leg's nickname, London replied, "If Cuthbert is giving you trouble, have him eliminated." From Spain, Hall made her way back to London, anxious to return to her work in France. This work had not gone unnoticed by the American counterpart of the SOE, the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), who recruited her soon after her return. Hall was now a member of the elite American undercover agency that employed 21,000 people around the globe, 4500 of them women. Most of these women worked in non-combat areas, serving in vital positions. A small percentage actually went into the field to work at overcoming the Axis power. And that was exactly what Hall wanted. Hall returned to France in the spring of 1944. The problem of her visibility was solved with a clever disguise: she went from being a trim, 38-year-old American woman to an elderly and robust French peasant. She transformed her limp into a shuffle, camouflaged her leg under ample woolen skirts, and again took up her one-woman campaign against the Third Reich. As the Nazi stranglehold on Europe had now become more tenacious, Hall's work became more militant. She organized, armed and trained three battalions of guerilla groups preparing them for work in sabotage. Together, they destroyed bridges and supply depots, bombed caravans of troops and weaponry, and continued to rescue Allied servicemen in need. Perhaps the most important, and the most dangerous, of Hall's work at this time were her radio transmissions. Unbeknownst to her or her resistance fighters in the spring of 1944, the greatest invasion in history was looming just weeks away and her reports of Nazi troop and headquarters locations proved invaluable in the D-Day planning. But Gestapo radio pinpointing had vastly improved since Hall's last duty in France and she was forced to be constantly on the move to avoid capture. The stress of knowing there was a price on her head and that she was the most hunted spy in Europe was immense, but her duty was to those who depended upon her and she persevered. As the war continued and the battle lines shifted, the work of Hall's resistance forces took on added importance. They provided daily intelligence on local conditions, confused the retreating Nazis and destroyed their supply and communication lines. As a result, Hall's organization was credited with killing over 150 Germans and capturing another 500. And she personally undertook the search and capture of a double agent whose treachery had resulted in the death of members of her group. This remarkable woman remained in France to see General DeGaulle and his troops march through a liberated Paris, and later to celebrate VE day - Victory in Europe. Her selfless acts of courage saved the lives of thousands of Allied servicemen and French citizens alike. Her belief in "liberty for all" was what motivated her to take on nearly impossible odds. She never thought of herself as special, but to those whose lives she saved, she was an angel. Her story should never be forgotten.

Excerpt

The old woman bent her gray head against the frigid wind blowing in from the English Channel as she struggled along the rocky Brittany seaboard. The French province had 750 miles of coastline, all of it inclement during the month of March. And on this particular March day in 1944, the wind seemed set on toppling her over. She was determined to stay her course, however, and shuffled on. ...Discussion Questions

No discussion questions at this time.Book Club Recommendations

Recommended to book clubs by 0 of 0 members.

Book Club HQ to over 90,000+ book clubs and ready to welcome yours.

Get free weekly updates on top club picks, book giveaways, author events and more