BKMT READING GUIDES

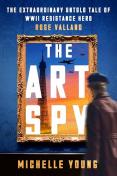

The Art Spy: The Extraordinary Untold Tale of WWII Resistance Hero Rose Valland

by Michelle Young

Hardcover : 400 pages

4 clubs reading this now

0 members have read this book

On August 25, 1944, Rose Valland, a woman of quiet daring, found herself in a desperate ...

Introduction

A riveting and stylish saga set in Paris during World War II, The Art Spy uncovers how an unlikely heroine infiltrated the Nazi leadership to save the world's most treasured masterpieces.

On August 25, 1944, Rose Valland, a woman of quiet daring, found herself in a desperate position. From the windows of her beloved Jeu de Paume museum, where she had worked and ultimately spied, she could see the battle to liberate Paris thundering around her. The Jeu de Paume, co-opted by Nazi leadership, was now the Germans’ final line of defense. Would the museum curator be killed before she could tell the truth—a story that would mean nothing less than saving humanity’s cultural inheritance?

Based on troves of previously undiscovered documents, The Art Spy chronicles the brave actions of the key Resistance spy in the heart of the Nazi’s art looting headquarters in the French capital. A veritable female Monuments Man, Valland has, until now, been written out of the annals, despite bearing witness to history’s largest art theft. While Hitler was amassing stolen art for his future Führermuseum, Valland, his undercover adversary, secretly worked to stop him.

At every stage of World War II, Valland was front and center. She came face to face with Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring, passed crucial information to the Resistance network, put herself deliberately in harm’s way to protect the museum and her staff, and faced death during the last hours of Liberation Day.

At the same time, a young Free French soldier, Alexandre Rosenberg , was fighting his way to Paris with the Allied forces battling to liberate France. Alexandre's father was the exclusive art dealer for Picasso, Matisse, George Braque, and Fernand Léger. The Nazis had taken everything from their family—their art collection, their nationality, their gallery, and their home in Paris.

Vivid and atmospheric, The Art Spy moves from the glittering days of pre-War Paris, home to geniuses of modern culture, including Picasso, Josephine Baker, Coco Chanel, Le Corbusier, and Frida Kahlo, through the tension-riddled cities and resorts of Europe on the eve of war, to the harrowing years of the Nazi occupation of France when brave people such as Valland and Rosenberg risked everything to fight monstrous evil.

In the spirit of Hidden Figures, with the sweeping narrative of The Rape of Europa and the depth of The Resistance Quartet, The Art Spy is an extraordinary tale of a female hero whose courage and tenacity in a time of violence and terror is an inspiration for us all.

Editorial Review

No Editorial Review Currently AvailableExcerpt

PARIS August 19–20, 1944 A torrential storm was pummeling Paris, turning the skies forebodingly dark over a city in the midst of a tense mandatory blackout. The clamor of thunder and the sounds of war rose to a crescendo as the battle for Paris began. After four brutal years of German occupation, the City of Light was allegedly going to be liberated. Cannons boomed, and shells whistled above the Seine, just meters away from the Jeu de Paume museum. Inside that nineteenth- century building, forty-five-year-old French art historian Rose Valland peered out from a slightly open window. The French Resistance had ordered a citywide uprising, and four thousand plainclothes police officers wearing tricolor armbands— the red, white, and blue of the French flag— invaded the police headquarters facing the Cathedral of Notre-Dame and took over Paris’s city hall, flushing out the Nazi occupiers. The Germans countered with bombs and blasts from their own armored tanks, trying to take the buildings back. Gunfire from street skirmishes rang out throughout the city. Bullets shattered windows and pierced buildings. German soldiers on foot attacked the street barricades built by Parisians out of burned-out cars, furniture, sandbags, barrels, cobblestones, pianos, and even urinals. From the Jeu de Paume, Rose could see dark smoke rising from the Grand Palais, the glorious palace of iron, steel, and glass on the Champs- Élysées that was used throughout the occupation for propaganda exhibitions. The Germans had sent a remote- controlled tank barreling into the building to kill the French Resistance fighters who had barricaded themselves inside. At just under five-and-a-half feet tall, Rose was dwarfed by the scale of the Jeu de Paume’s colossal arched windows, but there was nothing timid about her. Four years earlier, the Nazis had seized the museum to make it a headquarters for its art looting force, the Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg, to process the Jewish-owned art they had begun to plunder en masse in France. Her boss, Jacques Jaujard, the director of the Musées Nationaux— the French national museums—immediately ordered her to “remain at all costs at the Jeu de Paume museum” and covertly spy on the Germans. Iron-willed Rose was determined to see her orders through, but she did not know that she would risk her life for the next four years to achieve her mission. Rose had a reputation for being overly serious and too blunt for her own good, but her unflappability had proven useful in the war. She had learned to play the role of a nobody to the Nazis— not important enough to notice, not congenial enough to be flirted with, and too grave to be easily friends with. Unlike the other women who worked in the French museums, she didn’t bother much with her looks. Her most defining accessory was her round spectacles, which gave her an air of erudition. Although it was in vogue to wear one’s tresses in soft waves just above the shoulder, Rose simply brushed her brunette locks to the side and pulled them back in a neat bun. She left her eyebrows natural and mildly unkempt, unlike those popularized by cinema stars like Arletty and Danielle Darrieux, who wore them razor thin and drawn in darkly with pencil. Sartorially, Rose did her best to fit in. Though she would have much preferred to wear pants, she donned feminine, ankle-length dresses and blended in with the rest of the women in Paris—modest, traditional, and discreet. Still, the Germans had accused Rose of everything in their arsenal: sabotage, theft, and signaling to the enemy. They subjected her to invasive interrogations and searches, and even expelled her from the museum on several occasions. But she talked her way back in every time, explaining calmly that she was just a lowly employee of the French national museums who oversaw the building’s maintenance and the remaining art collection. In reality, she was one of the most well- educated art historians in France— and nearly every one of the German accusations had been true. Rose was also concealing another dangerous secret: she had been living for almost a decade with the love of her life, Joyce Heer, a British citizen who worked for the US embassy. Not only was her partner considered an enemy alien by the Nazis, but homosexuality was codified under Vichy French law as an “unnatural act.” Any misstep could lead to imprisonment, deportation, or worse for both Rose and Joyce. The Jeu de Paume was Rose’s first curatorial job after a decade of studies that took her all the way from her small countryside village in eastern France to Paris, the nation’s epicenter of fine art, and she felt personally responsible for the museum’s fate. Although it was not as prestigious as the Louvre, the Jeu de Paume had become a highly respected museum in the seven years Rose had worked there, in no small part due to her industriousness. It was renowned for its exhibitions on international and modern art, as well as for its fine permanent collection. It sat proudly on an elevated terrace in the Tuileries Garden in the heart of Paris at the corner of the Place de la Concorde and rue de Rivoli. The long rectangular building, designed like a Grecian temple, was built originally for court tennis during the reign of Napoleon III. Across the Tuileries was the Louvre. Now, the Jeu de Paume faced potential destruction, unwittingly situated at the center of the climactic final battle for Paris. The last of the German staffers in the Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg— the Reichsleiter Rosenberg Taskforce— had abandoned the museum in recent days as the formidable Allied forces advanced toward Paris. Rose and two French guards were the only people left inside the museum. Rose was ready to sacrifice her life to protect what was left of the museum’s permanent collection: paintings and sculptures by the likes of Salvador Dalí, Frida Kahlo, Wassily Kandinsky, Max Beckmann, Giorgio de Chirico, and many others. She and the guards would sleep on straw mattresses in the makeshift bomb shelter of the museum until it was all over, one way or another. But sleep was the last thing on Rose’s mind. She watched from the tiny opening in the window as German soldiers on the rue de Rivoli, the grand street that runs alongside the Jeu de Paume, shouted orders into an abyss of chaos. As night fell, tanks and military vehicles raced back and forth, readying for their last stand. Machine- gun fire popped all around the museum. Resistance fighters attacked the German dugouts and fortifications along the Place de la Concorde and rue de Rivoli. Sniper shots reverberated from the rooftops of nearby buildings. “A sort of frenzy of shouting and commands came to us,” Rose later recounted. The Jeu de Paume was just two blocks down the street from the luxurious Hôtel Meurice, where General Dietrich von Choltitz, the German commander in chief of Paris, was holed up. If he surrendered, Paris would be back in the hands of the French. The offices and apartments of the German Army, Navy, and Air Force stretched from the Place de la Concorde all the way to the Louvre. What had been a sumptuous playground for the German top brass was now their last line of defense. In the middle of the night, Rose looked on with dread as some fifty German soldiers arrived on the Jeu de Paume’s terrace. Through the downpour and lightning, the men installed rows and rows of criss-crossed wooden spikes wrapped in barbed wire, blocking the monumental doorway that once welcomed the likes of Hermann Göring, Adolf Hitler’s cruel right- hand man, and Alfred Rosenberg, the mastermind behind the Nazi Party’s most ruthless ideologies. “We were in an entrenched camp!” Rose later described with uncharacteristic emotion. Concrete blocks lay embedded in the ground just a few feet from the museum’s main entrance. A German armed sentry was posted in a new watchtower just twenty steps away, and to Rose’s dismay, he trained his sights on them. The Jeu de Paume’s complete isolation was clear. Rose fretted about what was to become of her beloved museum.Discussion Questions

1. What motivates Verne’s grudge against Rose? What past events or personal biases might have fueled his negative feelings toward her?2. Rose navigates and even assimilates with the elite social circles of France, but never fully fits in. Can you identify specific moments in her journey where this duality influenced her career? Did it help or hinder her professional development in Paris?

3.The exhibition in Munich was a direct response to the political climate of Nazi Germany. What do you think the exhibition was trying to achieve, and what does the overwhelming visitor turnout suggest about the public’s attitude toward the art displayed? Do you believe the exhibition was effective in fulfilling its mission? Why or why not?

4. The significance of Rose’s acquisition of Frida Kahlo’s portrait raises questions about their personal lives. After learning more about Kahlo’s life, what similarities can you draw between her and Rose? Why might Rose have been particularly drawn to this portrait?

5. On page 69, Rose describes the protection of French art as “one of the first reflexes of defense of our country.” What do you think she means by this statement, and how does it reflect the broader significance of art in times of war?

6. The role and importance of art during World War II is often overlooked in mainstream narratives about the war. How does exploring the events of WWII through the lens of art history enhance your understanding of the war’s broader cultural impacts, and its impact on both the individual and society? How does this perspective shift our view of

the conflict’s human cost and legacy?

7. Rose forms meaningful connections with women like Madeleine Bernheim throughout her career and involvement in the war resistance movement. How do these connections differ from her interactions with her male colleagues? What does this say about gender dynamics in the art world during this time?

8. Rose frequently risked her life to protect the Jeu de Paume and its collections. Given her lack of official recognition and compensation, what drives her to make these sacrifices? What do you think motivates her commitment to preserving art despite the personal cost?

9. Rose chooses to remain somewhat passive during the rise of resistance groups in art museums. What do you think influenced her decision to “keep her head down” (pg 134)? In your opinion, would she have been accepted if she had aligned herself with these groups?

10. Picasso and others show extraordinary acts of solidarity and protection during the war, such as when Picasso protects Matisse’s vault by fooling the German soldiers who came to search it. What are some key moments in the book where characters demonstrate defiance or selflessness in the face of danger? How do these actions compare to larger acts of resistance?

11. Rose and Joyce’s relationship, marked by secrecy and their shared closeted identity, adds complexity to their experiences during the Nazi occupation. How do the societal pressures on women, particularly in the context of their relationship, impact their lives before and during the war? How does this secrecy influence their choices and interactions, especially in a time when personal identities had to be carefully guarded?

12. Rose, a diligent documenter, never writes a single word about Joyce’s arrest—a striking omission given their closeness. How might the secrecy surrounding their romantic relationship influence Rose’s decision to leave this out of her private and personal records? What does this omission reveal about the personal struggles they faced?

13. Betrayal by close friends is a recurring theme in wartime, as seen through various examples in the book. Why do you think such acts of treason occurred during a time when people needed as much support and allyship as they could get?

14. Women often risked their lives for the war effort but received little recognition. Can you think of moments in the story where women were sidelined by their male counterparts despite their bravery? How might this impact their morale?

The liberation of Paris becomes tense for Rose when the crowd outside the Jeu de Paume turns against her. What might have motivated this sudden shift in the crowd’s celebratory sentiment, and what does this moment reveal about public perception in times of political upheaval?

15. In the Epilogue, we learn about Rose and Rorimer’s relationship post-liberation. Given Rose’s tendency to distrust others, especially men, what do you think allowed her to place so much trust in Rorimer?

16. Rose claims she did it all “to save a little beauty of the world” (pg 299). Do you think the aesthetic preservation of art was Rose’s primary motivation, or was there something deeper that drove her actions?

Book Club Recommendations

Recommended to book clubs by 0 of 0 members.

Book Club HQ to over 90,000+ book clubs and ready to welcome yours.

Get free weekly updates on top club picks, book giveaways, author events and more