BKMT READING GUIDES

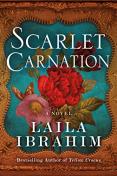

Scarlet Carnation: A Novel

by Laila Ibrahim

Paperback : 319 pages

0 club reading this now

0 members have read this book

1915. May and Naomi are extended family, their grandmothers’ lives inseparably entwined on ...

Introduction

In an early twentieth-century America roiling with racial injustice, class divides, and WWI, two women fight for their dreams in a galvanizing novel by the bestselling author of Golden Poppies.

1915. May and Naomi are extended family, their grandmothers’ lives inseparably entwined on a Virginia plantation in the volatile time leading up to the Civil War. For both women, the twentieth century promises social transformation and equal opportunity.

May, a young white woman, is on the brink of achieving the independent life she’s dreamed of since childhood. Naomi, a nurse, mother, and leader of the NAACP, has fulfilled her own dearest desire: buying a home for her family. But they both are about to learn that dreams can be destroyed in an instant. May’s future is upended, and she is forced to rely once again on her mother. Meanwhile, the white-majority neighborhood into which Naomi has moved is organizing against her while her sons are away fighting for their country.

In the tumult of a changing nation, these two women?whose grandmothers survived the Civil War?support each other’s quest for liberation and dignity. Both find the strength to confront injustice and the faith to thrive on their chosen paths.

Editorial Review

No Editorial Review Currently AvailableExcerpt

Prologue Naomi We make joy in spite of the indignity—or perhaps because of it. Delight in my well-lived life is a most satisfying weapon against the hate and trampling. God calls me to build the common good and make my own days glad. I do both with every breath I’m given. Naomi Wallace Chapter 1 May May 1915 “I don’t believe it would be wise,” May whispered in John’s ear. She resisted the warm tug of his body pressed against hers. His fingers released their tight grip on her skirt. He pushed against the mattress, cool air rushing into the gap between them, and looked into her eyes while he stroked the hair at the nape of her neck—a lovely shiver ran down her spine. “We are almost engaged,” he assured May. Her breath caught. He was finally expressing the sentiment she felt in her heart. “Are you certain?” He nodded slowly; desire filled his brown eyes. She took his face between her hands. Her thumbs caressed his cheeks as she gazed up at him. May combed her fingers through his sandy brown. He smiled down at her, his eyes sparkling with love. She brought her lips to his, ready to signal her consent with a passionate kiss, when the clock chimed the half hour. She dropped her head back on the mattress in his studio apartment. Not like this—when they were expected at Professor Kroeber’s for dinner. May exhaled hard and cleared her throat to push down her own desire. “Soon, I promise. I’ll be ready soon, but not tonight when we have to rush off.” He nodded and smiled, but the slight droop of his head told her he was disappointed. “I’m getting Margaret Sanger’s pamphlet on family limitation from my cousin on Sunday,” she reminded him, hoping her assurance would prevent hurt feelings. “You are practical, as always,” he said, and sighed. She shrugged. He gave her a peck on the lips and rose from his bed. May couldn’t read John’s emotions. Was he angry? She shouldn’t have let it get so far, but it was so pleasurable. She considered apologizing. John gazed at her like he knew her mind. “Don’t imagine my state to be anything other than pure devotion to you.” He exhaled. “I don’t want to rush into anything until you are as certain as I am.” A thrilling flood washed over her, causing her heart to race and her breath to shorten. This was love. May smiled, reached for his arm, and squeezed. This man who was both kind and intelligent was her treasure. She took a deep breath and forced herself to turn away from him—for the moment. *** May and John walked from his tiny apartment on the Northside of the University of California in Berkeley to Professor Kroeber’s house in the Berkeley Hills. In fifteen minutes it felt as if they’d been transported to the Napa countryside. John held her hand as they climbed steps through tall redwood trees and bright-green bunches of grasses. The staircase ended at a narrow street. May paused and turned around to catch her breath and take in the view. Spread out below, the bay sparkled in the sunlight. Tall, modern buildings in San Francisco rose on the other shore. Constructed since the 1906 Earthquake and fire, they were a testament to the resiliency of the city and its people. To the north the warm, brown hills of Marin County were marked by circles of oak trees and squares of bright-green farms. The Pacific Ocean sparkled beyond the gap of the Golden Gate until it ended under a thick blanket of gray fog. John took her hand. May’s heart sped up in anticipation. This was the moment she’d been expecting for weeks. They’d been dating for nearly a year and he was graduating in a few days. John gazed at her and swallowed. She smiled at him, her eyes shining in joy; she nodded in encouragement for his formal proposal. He bit his top lip, and inhaled, readying himself to ask. Then he turned back to the vista. Her stomach dropped. “Nearly as splendid as the view from Indian Rock,” he declared. “I don’t believe there’s such a lovely view in all of San Francisco. Don’t tell my parents, but this is the more favorable side of the bay.” She took a deep breath to slow her hurt heart. Hiding her disappointment and misunderstanding, she bantered, “I won’t tell your family, nor anyone else from that city. More than enough of them inundated Oakland after the earthquake. I don’t need to encourage more to make the East Bay their home.” “Am I such a burden to your fair city?” he asked. She paused, tapped her lip with her finger, and stared upward as if in deep thought. “I suppose there is room for you, but only you.” She laughed and kissed his warm lips. She intended a peck, but his hand cupped her cheek and she found herself lost in the moment. When they broke away his shiny eyes expressed the longing in her heart, confirming her understanding he shared her deepest desire. May had to trust he was waiting to secure work. On Wednesday, John would be conferred a Doctorate of Philosophy in Anthropology. Ideally, he would get a professorship in Northern California at Stanford University or Mills College to be close to their families—his in San Francisco, hers in Oakland. If not, he would seek a position at one of the many institutions of higher education in Southern California. A degree from the University of California was so well regarded that she was confident they wouldn’t need to leave the state. After graduating from Oakland High School two years ago, May applied for jobs only at the University of California. As the secretary at the Department of Anthropology she met many wonderful college men. A few months of flirtation with John turned into the respectful romance she desired and would soon become a lifelong marriage. She shook her head to clear it and reminded him with a smile, “We don’t want to be late.” He turned left, walking a few yards down the street to the brown shingled home where Professor Kroeber, his advisor and her boss, lived. They were gathering in celebration and farewell. As a secretary in the department, she’d never received an invitation to a coveted dinner party at Professor Kroeber’s home, but she was confident she would be warmly welcomed as John’s date. Professor Kroeber was forward thinking about social equality and never showed any class prejudice toward May. She was proud to have supported his research and would miss working with him. Mrs. Kroeber, a plain but confident wife, ushered them into a stunning redwood-paneled living room. “A genuine Maybeck!” John whispered into her ear, reminding her that the renowned architect he so admired designed this home. “Almost the equal of a Julia Morgan design,” May retorted. He laughed, as she intended. She was forever championing the up-and-coming female architect. They were unlikely to ever afford a custom home, but they enjoyed conversations about designs. They were both favorably inclined toward the modern simplicity of the arts and crafts movement rather than the ornate Victorians they each lived in as children. Thomas King, another graduate student, and his date, Judith Hunt, were seated on a couch across from Professor Kroeber. Ishi was seated by the professor in a high-backed upholstered chair. His dark hair and skin stood out from the cream fabric. She glanced down. His bare feet spread on the red Oriental rug, an amusing juxtaposition with his Western suit. A small, sweet smile spread across his face though he didn’t look at May. In the custom of his people he didn’t make eye contact or speak directly to her, a woman not in his family; nevertheless, he conveyed warmth and calm. Ishi’s life was as heartbreaking as it was inspiring. For several weeks in 1911 he made the headlines in the newspaper. The whole state, perhaps the entire nation, followed his story with great interest. Nana Lisbeth had been so moved that tears ran down her cheeks as she read the account in the Oakland Tribune. Ishi walked into Oroville, California, barefoot and emaciated—wrapped in mystery because he spoke no English. Before she worked there, the professors in May’s department read about his plight in the newspaper and arranged for his release from jail to the university. In time Ishi explained he was the last of the Yahi, a tribe of Native Californians. During the Civil War, in 1861, his community was nearly decimated in the Three Knolls Massacre. A small band hid in the hills for five decades, dying one by one until Ishi was alone. Close to starving, he revealed himself to an uncertain fate in a society that destroyed his people. In the four years since he emerged from hiding he lived and worked in the University of California Anthropology Museum at the Golden Gate Park in San Francisco. Nana Lisbeth and Momma were very impressed May met him more than once, when he came to the department office to meet with Professor Kroeber and his students or to make a record of the Yahi language and mythology. On Sundays Ishi displayed his skills in bow making, arrowhead carving, and fire starting at the museum to the public. May had yet to see his survival talents, but planned to when she attended the Panama-Pacific Exhibition, the months-long, world-famous exhibition in San Francisco celebrating the opening of the Panama Canal. Mrs. Kroeber stood in the doorway and pronounced, “We are all here and dinner is ready, so please come to the table.” May flushed at the memory of why they were late. She raised her hand to her face, as if she could feel that her cheeks were red. She didn’t dare look at John for fear of blushing further. Over a simple dinner of roasted chicken and potatoes they discussed the news of the department. “Tell them our news,” Judith prodded Thomas. “I’ve accepted a position at Whittier College in Los Angeles County,” he declared. “Congratulations!” Mrs. Kroeber said. “Wonderful,” John replied, but May heard the jealousy in his voice. “Well deserved,” Professor Kroeber chimed in. “Judith and I will be married next week and then head south at the end of June,” Thomas declared. Envy shot through her. She wanted her future settled too. May took a deep breath to calm her heart, forced a smile, and added her congratulations. John squeezed her hand. Judith looked at May. “You’ll be my maid of honor, won’t you?” “Of course,” May replied, but her voice sounded hollow to her own ear. She enjoyed Judith’s company well enough, but the woman she went on double dates with wouldn’t stand by May when she got married. That honor would go to her cousins: Elena and Tina. Judith didn’t have any family near, so it made sense that she asked May. “Saturday, two o’clock at the campus chapel. We hope you all will be there,” Thomas said to the whole table. To May and John he said, “Our joint excursion to the Pan Pacific Exhibition shall be our last double date, I’m afraid.” A week from Sunday they were ferrying across the bay to visit the fair. John said, “May is looking forward to seeing your skills on display, Ishi. I have told her that you seem to make fire out of air.” Ishi gave a single nod. Professor Kroeber spoke up in his authoritative voice: “I was most grateful to have Ishi’s skills as a counterbalance to the eugenicists. Their excessively large booth was very well funded by Kellogg. They advocate for limiting reproduction to the original stock of this nation and forbidding immigration except from Northern Europe. Their dangerous Darwinian argument will lead to forced sterilization.” Disgust in her voice, Mrs. Kroeber explained, “They actually advocate for a eugenics registry to create a pedigree of breeding pairs—for humans. It seems they would make it illegal for a Norwegian to marry a Greek if they were able.” May gasped. She’d known there was a huge rift in the anthropology field, but she didn’t realize the eugenicists were so well organized and extreme. John replied, “Wouldn’t they be horrified by our student body—women, Negroes, Chinese?” The table murmured their agreement. The University of California was extremely proud that the student body was not limited to White men like so many institutions of higher education. It had been forward thinking from its very foundation. The conversation continued and the evening flowed by quickly. May studied Mrs. Kroeber, watching how she kept everyone engaged with ease. She asked questions, made comments, and changed topics as needed. She balanced being the cook, the maid, and the hostess with grace. May took this opportunity to learn, since she would be in this role soon. *** “Not one mention of the Lusitania,” May said as they rode the trolley to her home a mile below campus in the Santa Fe neighborhood. The development of small craftsman homes, far from the Oakland city center, was one of the many springing up along the train route between Oakland and Berkeley in the past ten years. Days after May graduated from high school, in 1913, Nana Lisbeth sold their boardinghouse close to downtown to purchase this home in the suburbs with modern amenities such as electricity and a gas stove. The two-bedroom bungalow was a bit tight for the three of them but would be the right size for Nana Lisbeth and Momma once May was married and had formed a separate household. “Honestly, I avoided the topic because it would have taken up the entire evening’s conversation,” John replied. “We only have a few more days to think about our research together. The speculation about joining in the European War is growing tiresome. We will or we won’t. I am not sure how it will affect my life.” “I agree. There are good arguments on both sides, and my opinion won’t sway our leaders one way or the other.” May switched topics. “Professor Kroeber’s description of the eugenics booth was disturbing. I can hardly imagine something that offensive in San Francisco in 1915.” “We’ll see for ourselves soon enough,” John said. “So many of our colleagues do not respect other races at all. I want to see their evidence for myself—though I know most of it is derogatory and inaccurate.” May was heartened that they agreed on such a controversial topic. They stopped walking where the stairs to her house met the sidewalk. It was late, too late, for May to invite John in. However, only the front porch light was on; Momma and Nana Lisbeth were most likely asleep, so May leaned in to kiss her beloved. When she pulled away, her heart pounded and her lungs were tight in the best way. She whispered in his ear, “I cannot wait for the day when we won’t have to part at night.” He squeezed tight, then released her with a heavy sigh. She shared his frustration . . . and longing. This was a major step, but she was ready to take it with him. As long as he was devoted to a future together and she used the means of preventing a pregnancy, she saw no reason to delay the pleasures of the body. Fortunately her cousin Elena’s copy of Margaret Sanger’s pamphlet, the very one on family planning that caused the activist for women’s empowerment to be imprisoned, would be in her hands soon. Mrs. Sanger, the most celebrated advocate for birth control in the nation, was a hero to May and most Unitarian women. May agreed wholeheartedly with Mrs. Sanger’s powerful words: Enforced motherhood is the most complete denial of a woman’s right to life and liberty. At the front door May looked back for a final wave. John’s lusty smile confirmed parting was hard for him too, and made her heart dance. Such sweet sorrow, she thought with a smile. May forced herself to turn away from him into the dark, quiet house. She rested against the closed door and stopped for a deep breath to calm herself. Only a few more days of this, she reassured herself. She took off her shoes and got ready for bed in her stocking feet. As she climbed into bed her mother turned over and whispered, “Good night, May.” May exhaled. “Good night, Momma. Sleep well.” May lay in bed, her back to Momma, longing for the day she would be climbing into bed next to her husband, Dr. John Barrow. *** The next morning Nana Lisbeth carried clippers and straight pins when they walked out the door for church. They stopped in their front garden and she went to work harvesting the blooms she’d nurtured for this day—Mother’s Day. The white-haired woman clipped one carnation followed by another until all of the white blooms, representations of love and protest, were in her hands. She clipped two scarlet ones but left the rest. At May’s church, congregants wore white carnations to honor deceased mothers and scarlet ones to honor living ones. The tradition began after the Civil and Prussian Wars when Julia Ward Howe encouraged mothers to wear white carnations to protest sons being sent to be killed in battle. Decades later, Anna Jarvis popularized the symbol as an honor to motherhood, going so far as to successfully advocate for a federal law making the second Sunday in May time to honor mothers. With the war raging in Europe, many congregants would wear white carnations for two reasons: a protest against the United States joining the fight and to honor their deceased mothers. The symbols were getting muddled. Nana Lisbeth handed Momma a pin and a white carnation. She touched her hand to her chest and said, “For Ann Wainwright.” Momma attached the white flower to Nana in honor of her mother. Ann Wainwright was only a name to May. Nana’s mother, father, and brother Jack died on the other side of the nation in Virginia long before May was born. They were characters in Nana Lisbeth’s stories but didn’t feel like family. Nana Lisbeth held out another white flower for Momma to pin on her. “For Mattie Freedman.” May smiled. This flower honored Nana’s enslaved caregiver from the family plantation—Fair Oaks. Nana Lisbeth called Mattie her “real mother,” the person who shaped her the most. May hadn’t met Mattie’s son Samuel or his descendants that lived in Chicago, Detroit, and Memphis, but the branches of their two families that lived in Oakland remained close. They saw each other a few times a year. Auntie Jordan, Cousin Naomi, and Cousin Willie were extended family—a treasured part of the fabric of love woven into their life, less close than Uncle Sam and Auntie Diana or her cousins, but definitely beloved family. “And for peace.” Nana Lisbeth held up another white flower for Momma to pin onto her chest. Each flower placed on Nana’s chest seemed a prayer. Nana Lisbeth turned to face May and pinned a scarlet carnation on herself. “To honor your mother.” May heard the command in her grandmother’s mature voice. She’d not been very gracious to Momma lately. She believed it only in response to her mother’s attitude, but Nana Lisbeth wanted them to be kinder to one another. May was ready for more distance, to share a bed with her husband rather than her mother. She wanted her own home and family separate from her elders. Momma hadn’t done anything wrong; May simply wanted a different life than Momma had settled for. After her husband died Momma never remarried, never traveled, and served people: first in the boarding home and now as a grocery store clerk. May was going to be a professor’s wife, surrounded by interesting conversation and intellectual rigor, nothing like Momma—a store clerk living with her elderly mother. May was grateful for the life her mother and grandmother gave her after her father died. She knew they worked hard, but she wouldn’t be held back by her mother’s ennui. Nana Lisbeth held out a white carnation and raised her right eyebrow in question. Did May want to wear one for peace? May sighed. Of course she wanted peace, but was she against this war? There were sound arguments for staying out of it and equally strong ones for joining in the fight. She’d yet to decide where she stood and didn’t want to wear one simply to go along with a common sentiment. She shook her head. “I will have one of each,” Momma declared. Nana Lisbeth handed over two carnations, which Momma pinned herself. *** “Did he propose last night as you’d hoped?” Nana Lisbeth asked May as they rode the train down Telegraph Avenue. They were going for worship at the Unitarian Church in Oakland. The Berkeley church was closer to their new home, but her mother and grandmother were loyal to the congregation where they’d been active since they’d become involved in the suffrage movement in the 1890s. May found their attitudes when it came to women’s freedoms to be both amusing and annoying. They assumed she would get married and live independent from them after high school, but seemed to think she was being too independent in accepting John. She suspected it was because he refused most of their supper invitations. He was too busy with his studies, and he didn’t find her family interesting enough to have dinner with them every week. He’d come often enough for May—even to a Sunday supper where he met Auntie Diana, Uncle Sam, and her cousins. May shared their fears that her marriage to John might take her far away, but they needed to accept that she was an adult and would be living her own life separate from them. Neither Nana Lisbeth nor Momma were married. When she was an infant, May’s father traveled for work to Hawaii and died there. They didn’t even have a grave to visit. Momma was so disturbed by his absence that she never spoke of him, not on the anniversary of their wedding or his death or on his birthday. May only knew two facts about her father: he immigrated alone as a young man from Germany and he died alone in Hawaii. He was a gaping hole in her heart and in her mind. As much as she wished Momma was strong enough to speak of him, she wasn’t. In contrast, May’s childhood was filled with stories about Grampa Matthew and the produce business he and Nana Lisbeth started after they moved to Oakland in 1873. She heard so many stories about him at family gatherings that she felt as if she’d met him. Every week Nana Lisbeth visited Grampa Matthew’s grave in Mountain View Cemetery. May accompanied her when she was young, but the habit fell away as May matured. May simply shook her head in answer to her grandmother’s question. She didn’t elaborate because she wasn’t interested in either defending John’s actions or hearing their opinions about her life. *** May’s aunt, uncle, and cousin were already seated in their usual row in the sanctuary. She took the chair next to her cousin, and leaned over Elena’s belly and said, “Hello in there!” Elena laughed and rubbed the small protrusion. “How are you feeling?” “The nausea has dissipated at last—and I have energy again. Hallelujah!” Elena declared. “Wonderful.” May beamed. She and Elena were as close as sisters—especially since Elena’s older sister Tina moved to Martinez four years ago. May confided in Elena more than anyone else in her life. They saw each other at least once a week—at church followed by Sunday supper at Aunt Diana and Uncle Sam’s. Hopefully Elena becoming a mother would bring them even closer. May intended to be as helpful as possible. “How was the dinner?” Elena asked. “Lovely,” May declared and then added, “And a touch disappointing.” “No question?” May shook her head. “He paused our journey at the top of a staircase. We took in a gorgeous view of the bay. He pointed out where he thought his home was. When he cleared his throat in a way that cause me to believe this might be it, my heart raced in my throat. But we only kissed again and moved on.” May let out a sigh. “What is he waiting for?” “He wants a settled position before he makes such a request; I’m sure of it. His future is still uncertain.” “Well, that is practical,” Elena said, her voice cheery, but her eyes held a different sentiment. “What?” “We always spoke of our children being as close as sisters, like us. I am happy for you. John is a successful and kind man. But selfishly, I don’t want you to move away.” May teared up. “I agree. It is at once thrilling and horrifying to imagine moving. I still hope a local college will extend an offer.” Reverend Simmonds walked down the aisle and worship began with one of May’s favorite hymns: “My Life Flows on in Endless Song.” She always took this choice in music as a sign that it would be an enjoyable service. She looked at the beautiful stained-glass window of the sower and the huge redwood beams above her head. Sorrow bubbled up. May would miss worshipping with her family each week. John showed no inclination to attend regularly, though he did express enthusiasm for Unitarian values. Mills College, she hoped or prayed—sometimes it was hard to tell the difference. She would hold out hope that John would be offered a position at Mills so they could stay in Oakland. May hooked her arm through Elena’s and gave her a squeeze. After the closing hymn and benediction the family walked to Uncle Sam and Aunt Diana’s home for Sunday supper. Wanting privacy, May and Elena trailed behind the group. May whispered in her cousin’s ear, “Do you have the pamphlet?” “As promised.” “It worked for you, right?” May confirmed. Elena nodded. “For two years, until . . .”—Elena rubbed her belly—“it didn’t.” She laughed. “Peter and I are mostly ready. In an ideal world this would have happened after our house was more finished, but we will make do. Even though she’s a surprise, she’s a welcome surprise.” “You sound so certain you are having a daughter.” “If I say it enough God will grant my prayer.” May laughed. “You know that’s not how it works.” “So the scientists say. But my Bubbi is certain God is still deciding if there’s a boy or girl coming.” May laughed again. “I’m happy to use science when it suits me and folklore as I see fit,” Elena declared. May said, “Remember when you used to insist you were going to marry another girl?” Elena looked wistful. “Oh, to be young and naïve.” “I’d insist, ‘Two girls can’t get married!’” “And I’d argue back, ‘Why not?’” “And I’d say, ‘I don’t know any girls that are married.’ And you would declare, ‘You will when I am.’” They both laughed. Elena returned to the topic of family planning. “The pamphlet isn’t very long. It’s written in the plainest language and easy to read. I used the sponge soaked in carbolic acid and glycerin. I’ve never found a place to purchase a pessary—though they sound more pleasant. I always douched with Lysol after the act. I didn’t always take the laxative as Mrs. Sanger recommends.” Elena made a face as she rubbed her belly. She continued, “And I think that’s what got us this little treasure.” “It sure is a lot of work!” May observed. “Less work than having a baby, and if you have a good man, more fun.” Elena laughed, her mouth wide and her head thrown back. She looked like Aunt Diana—full of life and joy. And the holder of a secret that May was ready to be in on.Discussion Questions

1. If you’ve read the companion novels (Yellow Crocus, Mustard Seed, or Golden Poppies) was this a satisfying part of these characters’ journeys?2. What do you think Laila Ibrahim’s purpose was in writing this book? What ideas was she trying to get across?

3. Did May’s desire to end her pregnancy change your understanding of her character?

4. Why do you think Laila Ibrahim chose to have Ishi as a historical figure in this novel? What does he represent to the other characters? Is there any person that plays that role in your life?

5. Laila Ibrahim writes about diverse characters struggling to overcome personal and systemic hardships. She does not share the characters’ cultural background. Is it problematic for an author to write about cultures that are not their own?

6. Did any historical details surprise you?

Book Club Recommendations

Recommended to book clubs by 0 of 0 members.

Book Club HQ to over 90,000+ book clubs and ready to welcome yours.

Get free weekly updates on top club picks, book giveaways, author events and more