BKMT READING GUIDES

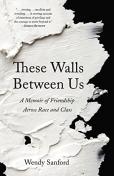

These Walls Between Us: A Memoir of Friendship Across Race and Class

by Wendy Sanford

Paperback : 328 pages

4 clubs reading this now

0 members have read this book

Introduction

From an author of the best-selling women’s health classic Our Bodies, Ourselves comes a bracingly forthright memoir about a life-long friendship across racial and class divides. A white woman’s missteps and necessary lessons, and a Black woman’s complex evolution, make These Walls Between Us a “tender, honest, cringeworthy and powerful read.” (Debby Irving, author, Waking Up White.)

In the mid-1950s, a fifteen-year-old African American teenager named Mary White (now Mary Norman) traveled north from Virginia to work for twelve-year-old Wendy Sanford’s family as a live-in domestic for their summer vacation by a remote New England beach. Over the years, Wendy's family came to depend on Mary’s skilled service—and each summer, Mary endured the extreme loneliness of their elite white beachside retreat in order to support her family. As the Black “help” and the privileged white daughter, Mary and Wendy were not slated for friendship. But years later—each divorced, each a single parent, Mary now a rising officer in corrections and Wendy a feminist health activist—they began to walk the beach together after dark, talking about their children and their work, and a friendship began to grow.

Based on decades’ worth of visits, phone calls, letters, and texts between Mary and Wendy, These Walls Between Us chronicles the two women’s friendship, with a focus on what Wendy characterizes as her “oft-stumbling efforts, as a white woman, to see Mary more fully and to become a more dependable friend.” The book examines obstacles created by Wendy’s upbringing in a narrow, white, upper-class world; reveals realities of domestic service rarely acknowledged by white employers; and draws on classic works by the African American writers whose work informed and challenged Wendy along the way. Though Wendy is the work’s primary author, Mary read and commented on every draft—and together, the two friends hope their story will incite and support white readers to become more informed and accountable friends across the racial divides created by white supremacy and to become active in the ongoing movement for racial justice.

Editorial Review

No Editorial Review Currently AvailableExcerpt

Introduction I GREW UP IN THE NORTHEAST UNITED STATES, AMIDST white people who thought ourselves a world apart from the white supremacists of the Ku Klux Klan—the violent, radical fringe. And yet, I grew up embedded in racist violence myself, just of a variety that was polite and normalized in American life, in which every institution advanced white people at the expense of people of color. I also toddled my first steps into a fraught zone between my white mother’s blue-blood, owning-class family and my white father’s hard-scrabble-farm Georgia roots. I channeled both my mother’s assumptions of superiority and my father’s urgent, resentful aspiration to rise. My parents united in the project of training me to become a white, upper-class, wealthy woman. They only half-succeeded. As an adult, I thrived in the women’s health movement, joined the Quakers, immersed myself in writings by people of color, and fell in love with a woman. I am grateful to the many magnets that drew me outside my family’s elite bubble and landed me in a more humane life. Most centrally, I am grateful to Mary Norman, whose friendship is the magnet that has mattered the longest. More than sixty years ago, in the mid-1950s, a young African American teenager named Mary White traveled north from Virginia to work for my family as a live-in domestic worker during our summer vacation. Mary was fifteen, I was twelve. As the Black “help” and the privileged white daughter, we were not slated for friendship. Employers like my mother used the word “friend” to manage domestic workers, not to connect with them. Soon, however, came the dynamic social movements of the 1960s, ’70s, and ’80s: the civil rights movement, multi-racial feminism, and liberation theology. These movements opened friendship as a possibility between Mary and me. We stepped into that opening. Across the stark differences of race and class between us, we began to shape a bond. Some thirty years after we met, in the late 1980s, Mary declared that we should write a book about our friendship. She, more than I, understood how many rules of the dominant culture we had violated in our journey towards becoming friends— unwritten rules of domestic service, carefully policed barriers between white and Black, between rich and poor. “No one will believe our story,” she said. At the time, we had been sharing novels and essays by Toni Morrison, Paule Marshall, Alice Walker, Audre Lorde, and Alice Childress. Especially electrifying for us both was Anne Moody’s Coming of Age in Mississippi, which Mary said came the closest to expressing her own experiences growing up Black in the rural South. I had worked with a team of women as coauthor and editor of Our Bodies, Ourselves, a feminist resource on women’s health and sexuality. All this made Mary’s suggested writing project seem possible. We even fantasized being invited by Oprah to appear on her new-at-the-time TV show. These Walls Between Us is not the book Mary and I imagined we might write together. The book would not exist without Mary, based as it is on innumerable conversations between us—by phone, in person, via email, and, in later years, via texting. Mary has read and commented on every draft, but These Walls is very much my story. It focuses on my often-stumbling journey towards seeing Mary more fully across the socially constructed barriers between us—that is, towards being a truer friend. It is written with a white readership in mind, to invite white readers to join me in exploring our relationship to white supremacy culture. It’s 2020 as I finish this book. Mary is eighty years old, I am seventy-six. On weekly phone calls, we carry on about politics and family like the observant, caring old women we are. As we vented about the Trump presidency, Mary said of the book, “I think of the climate we are living in now, all the hateful things mostly young white males are doing that fall into the category of hate crimes, putting a wedge between people. The people who elected President Trump want to take the country back to the good old days. This book can show what those days were really like.” For my part, I hope These Walls Between Us will also be a testament to the power of love that has kept us, each in our own way, reaching across the obstacles arrayed against our becoming close. I hope that it will inspire readers to examine the barriers and possibilities in their own cross-racial and cross-class relationships. one White People Swimming I JUMPED UP WHEN I HEARD MY MOTHER’S STATION WAGON scratching along the prickly bushes that crowded the driveway of the seaside rental in Nantucket, summer of 1956. I’d been so moody and mopey that morning that my mother had accused me of “treating this nice vacation like a prison sentence.” She’d driven alone to the ferry dock in town to pick up her new summer helper. The screen door to the kitchen squeaked open, slammed shut. “Damn that door,” my mother said. A quiet, shy voice. “I can fix that right up for you, Mrs. Coppedge.” I slipped into the kitchen to find a slender teenager with dark brown skin, her body shapely in a black skirt and sweater. “This is Mary,” my mother said. I thought I saw a quick, shy “hello” pass through Mary’s large, brown eyes, before she started looking around the kitchen. She scanned the rack of pots and pans, the counters and the double sink, the clothes washer, the long pine table with a built- in bench along two sides. She looked back over her shoulder to the empty clothesline outside the screen door. I hadn’t looked at Wendy Sanford all these things together before. When she finished her inspection, Mary straightened her back and looked resolute. Years later she would tell me she’d been summoning courage. She didn’t know how to work a gas stove. She worried that my mother would be upset by this. She felt alone. I darted forward to tug at the handle of Mary’s suitcase. I wanted to help her take the bag to her room, but I couldn’t lift its weight. “Let me do that,” Mary said matter-of-factly. She reached down and eased my fingers aside. This first summer vacation on Nantucket was a long time ago now—and an experiment. My mother’s upper-class family had a legacy of lengthy, expensive beachside vacations. My striving, corporate-lawyer father could finally afford a month-long rental on a secluded Nantucket beach. Friday evenings, he would fly in for the weekend, braving the relatively new commercial airlines and the island’s notorious fog. My energetic eight-year- old brother would go to overnight camp on the Cape, so that my mother wouldn’t have to amuse or contain him. Twelve years old and more bookish, I’d spend the month with my mother. As an- other perk of my father’s increasing affluence, my mother would have “help.” I imagine my mother calling around to her friends in Princeton, New Jersey, where we lived, seeking the name of a “good, hardworking girl.” A young Black woman named Betty Phipps, who did domestic work for my godmother, recommended her niece from Elk Creek, Virginia. On the morning I’m remembering, Mary White’s arrival marked the perfection of my parents’ plan—and a step forward in Mary’s own aspirations. Mary carried her heavy suitcase into the bedroom next to the kitchen, and I followed. Mary’s room, like mine, had two single beds. The quilts were faded, the walls yellow pine. Two brand new shapeless white cotton uniforms hung on the closet door, price tags still attached. My mother had bought them sight unseen, guessing at Mary’s size. I didn’t wonder at the time whether Mary had worn such uniforms before (she hadn’t) or how she felt, seeing them hanging there like rules and regulations. While my room looked out over the ocean, the view from Mary’s bedside window featured the empty laundry line strung between two poles in the back yard. Her north-facing window looked out on Nantucket’s signature Rosa rugosa bushes, densely green and thorny, with occasional pink blooms. On tiptoe, you could glimpse the sea. Mary lifted her suitcase to the spare bed. There was a flumping sound as the mattress sank. I leaned against the door- way and watched. “Can I help?” I asked.?Mary widened her eyes and shook her head no.?“Can I stay?” I did not consider that Mary might want privacy.?She shrugged almost imperceptibly. “If you want to,” she said.?We looked for a while at Mary’s suitcase on the narrow bed. “Want me to open it now?” she asked.?I nodded. I must have known, without anyone telling me directly, that Mary wouldn’t feel free to say no. She sighed, snapped open the two metal clasps, and slowly lifted the top. I spotted a few clothes—a nightgown, dark slacks, and what looked like a lightweight navy-blue jacket. Then the weight: two bottles each of an unfamiliar brand of shampoo and conditioner, a six-pack of orange soda, and a brown AM-FM radio with the cord wrapped neatly around. Mary lifted the radio out like a baby and set it gently down on the bedside table. “Nice radio,” I said. She startled at my voice. “Oh!” Slowly she drew her eyes away from the treasure. “It was a gift.” “For what?” I asked, curious to the point of intrusion. I gave my gracelessness no thought. She blinked. “High school graduation,” she said. She turned her head so that I couldn’t see her full face. Mary seemed young to have graduated from high school. Decades later, she would take me to the one-room, uninsulated building in Independence, Virginia, the only school that the state of Virginia had provided for Mary and the other local Black children to attend. “We were all in this room,” Mary told me then, “everyone at some different level of learning, with the big stove in the middle, and the teacher going back and forth between the groups. It was not a good time.” I could picture Mary, clustering with her fellow students around the pot-bellied stove in winter, burning hot on one side of her body and bone- chilled on the other. With no extracurricular activities, few books, and one teacher for students from five to fifteen, Mary quickly mastered everything the school could offer. There was no expectation, in that era, that a young Black woman needed further education. The only jobs open to her were like the one Mary was starting with my family. Virginia finished schooling Mary long before she received the education she wanted or de- served. I hung around in Mary’s doorway, not thinking that she had just traveled nine hundred miles and might be tired. In what would become the pattern for many years ahead, Mary turned her attention to me. “You having a good time here so far?” I was about to complain that I didn’t have any friends yet, when my mother called from the living room. “Mary’s had a long trip. Why don’t you let her unpack in peace?” Mary was at her door in a split second. “I don’t need more time, Mrs. Coppedge. I’m ready to do whatever you want.” As she headed into the kitchen, I turned to plug in her radio. In a small vase on the bedside table, I noticed three daisies and a wild rosebud that my mother must have picked and placed there that morning. My mother and her friends called their servants “girls,” as a marker of their own superiority. And yet, though she was only fifteen, Mary was not free to be a girl. The limits our society placed on her were rushing her into womanhood. Mary’s family back in Virginia counted on her earning power. She was already in the labor force. She did not have the luxury of being a child. Nothing in my affluent and exclusively white world could help me understand the relentlessness of the work Mary had done already in her short life and would be doing for us. Mary would wash and clean, straighten and replace, cook and prepare. Mary’s work, and the work of women like her, helped sustain my childhood and my enjoyment of it. In the purposeful ignorance of white people both then and now, I asked Mary little that summer about her journey to my mother’s kitchen. Years later, after I learned to inquire and to listen, Mary described the nine hundred miles she traveled to the re- mote Nantucket beach. Her mother, Alice Johnson, put her on a train from Wytheville, Virginia, to Trenton, New Jersey, where Mary’s aunt Betty Phipps had moved some years earlier in search of better work. Phrases like “long train ride” and “first time away from home” fail to capture the indignities of Mary’s trip. Racist regulations at that time forced Mary’s mother to put her on a train car designated for Black people. The dining car was open to whites only, Mary told me, so her mother sent her with a “peanut butter and jelly or baloney sandwich and a slice of cake, maybe a candy bar.” Many hours later, Mary’s Aunt Betty met her at the Trenton train station and took her home. Mary reports that this break in the journey north felt welcoming and protective after the abuse and insult of segregated transport.1 The historic Great Migration in the United States was made up of African Americans like Mary’s Aunt Betty, and then Mary herself, who moved north and west to escape the Jim Crow South, hoping for better employment and a freer life. Mary, like others who’d gone before her, received welcome and help from family members already arrived, a job secured by a relative, and practical advice. Mary remembers her Aunt Betty’s advice: “Mrs. C. is a very nice woman and will be good to you—just do what she asks.” The next day, to launch her young niece into her first live-in job, Aunt Betty drove Mary to my family’s home in Princeton. My mother, who was already on Nantucket, had hired an off- duty police officer, Norman, to drive Mary seven hours further north, to the ferry dock in Woods Hole. From my mother’s perspective, hiring a white, off-duty cop was a resourceful strategy for safely transporting Mary, who was very young, unfamiliar with the North, and unaccustomed to travel. I imagine my mother had no thought that Mary might be afraid of this man. 1 The National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, DC, exhibits a railway car from the long era of segregation. Stepping on, one notes immediately the stark differences in comfort and de?cor between the whites-only and colored-only sections of the carriage. Mary’s first trip north came months after the Interstate Commerce Commission finally ruled that racial segregation in public transportation violated the antidiscrimination section of the Interstate Commerce Act. Many states, however, were slow to comply. And yet, the all-white police departments back home in Elk Creek and Independence, Virginia, did little to make a girl like Mary feel safe. White police officers enforced the Jim Crow reg- ulations created to limit and control Mary’s family and other Black citizens—they could not be counted on to protect Black people from white violence. None of us could know, at the time, that, over decades of supplementing their incomes by moon- lighting for my parents, Mary and Norman would come to count each other as valued friends. Mary’s first burden of service to my family, however, was to climb into an unknown car and travel seven hours through unfamiliar landscape with an unknown white policeman. “It was a long ride to Woods Hole with Nor- man,” Mary remembers. “He hardly had ten words for me, so I was just looking out the window wondering, ‘What am I doing? Will I be okay so far from home?’” As Mary stood on the Woods Hole boat dock waiting to climb the gangplank to the huge, high-sided Nantucket ferry- boat, she experienced another facet of migration: the first shock of aloneness in an utterly white world. Mary had reason to feel wary, venturing by herself among so many white people. For Black people at that time, as could be said for today, being among unrestrained white people was dangerous. The previous summer, a white woman in rural Mississippi claimed that a four- teen-year-old Black boy visiting from Chicago treated her rudely. Her kinsmen abducted the boy, Emmett Till, and brutally tortured and murdered him. Till’s mother insisted on putting his mutilated body in an open casket, and Jet (the African American magazine) published the gruesome photo. News of what today is known as racial terror lynching flew through the Black community, motivating countless Black activists already poised to launch a national movement for civil rights.2 I imagine the collective trauma of this murder traveled with Mary on her journey north, perhaps even more so because she and Emmett Till were the same age. Emmett had ventured far from home. So, now, had Mary. The boat’s horn blasted. Enormous engines rumbled beneath Mary’s feet. The ferry churned into the waters of the Woods Hole harbor. Mary had never been on a boat nor seen the sea. She did not know how to swim. Where Mary grew up, the Elk Creek ran along the main country road for miles. Spring rains swelled the creek over its banks, flooding out the road and endangering those, mostly Black, who had to travel on foot. Water was a peril to be watched and feared. Mary’s three-hour ferry ride across Nantucket Sound was not something to enjoy, but a crossing to be anxious about. As she said years later, “I knew that if anything happened, that would be the end.” Mary remembers a miserable ride: “The younger folks looked and sniggered at me, while some of the older ones smiled, and others just looked through me. The horn was such a loud and piercing sound. After we started to move, I thought, Oh god, I am going to be sick. Mama, I am sorry, I want to go home.” I picture Mary sitting stiffly and anxiously inside the stuffy steamboat lounge, holding her hard-sided suitcase tightly as the boat pitched and rolled on choppy swells. Now, I ache when I think of the white kids sniggering smugly at Mary, yet I know that I was as ignorant as they were. Mary lugged her suitcase down the narrow gangplank to the 2 The goal of terrorists is to instill fear and to inhibit confidence and initiative; Mamie Till defied that goal. She chose an open casket funeral, so that her son’s mutilated face would inform the world about white men’s brutality to African Americans in the USA. Despite her courageous act, the two tried for murdering Emmett Till were quickly acquitted by a jury of all white men. Fifty years later, in 2017, the tragedy took on yet another dimension: Emmett Till’s accuser, Carolyn Johnson, confessed that she had fabricated the “incident.” Nantucket dock, an immigrant from one world to another. Trying to be brave as she stood alone in the rush of white travelers, she wondered if anyone would remember to meet her. Soon my mother arrived in the family station wagon, surveyed the crowd of arriving passengers through her big dark glasses, spotted the one Black teenager, and headed towards her new helper with a welcoming smile. “I followed her to the car,” Mary says now. “She kept up the happy chatter about the island, and what I would do, and not to worry. I remember saying I didn’t know how to cook much. ‘That’s fine, darling,’ she said, ‘I will show you.’” Safely in the car with her suitcase full of home, Mary felt fluttering worry about the job ahead. I picture her sneaking glimpses through the car window as her new employer drove deftly up and down across the rolling moors and scruffy vegetation of an unfamiliar land- scape. I doubt that Mary saw another person of color on that drive. I would later appreciate that the land my mother was driving Mary through was stolen country, former Native land, transformed by colonizers’ greed into the heart of whiteness. When I tell white people that I grew up in the 1950s, there is a knowing look. Oh, the conservative, conforming ’50s. Bobby socks and American Bandstand. Eisenhower, the president who had helped us win a terrible war; middle class women, smiling in their homes, tending their shiny new appliances; Elvis Presley shocking and thrilling female America with his gravelly, sexy voice, his gyrating hips. Oh, the ’50s. White veterans had been able to buy homes through the GI Bill and were forming families, building equity for the future. An ad on the era’s brand-new TVs showed a white family in Sunday clothes, walking together along a leafy suburban street, heading for church: “The family that prays together stays together.” In a communism-wary Washington, dangerous senators and the FBI scrutinized progressive men and women of all ethnic and racial groups—writers, actors, artists, activists—looking for shades of red. For Mary and her family in this same decade, the main theme of public life was not “I like Ike” or swooning over Elvis, but the struggle against Jim Crow—the panoply of quasi-legal rules and practices that constricted their safety, freedom, and livelihood. In the years just before Mary came to Nantucket, African Americans pursued major milestones in the struggle. In 1956, the first Black student entered the University of Alabama; Autherine Lucy was confronted by hate-filled riots that university trustees blamed on her presence. The university expelled her within months. A year later, in its historic Brown v. Board of Education decision, the U.S. Supreme Court at last declared segregated public schooling unconstitutional. In the winter of 1955 came powerful nonviolent resistance by those dependent on buses in Montgomery, Alabama, where Black citizens were charged full fare and told they had to move to the back, closer to the fumes. In a step long planned by ministers and other activists of Montgomery, Rosa Parks refused to give up her bus seat to a white rider. Her arrest sparked the yearlong Montgomery Bus Boycott, which was in full force during the summer that Mary first came north. When we met in my mother’s kitchen that summer, Mary and I came from different countries. My mother began teaching Mary how my father liked his coffee, his pork chops, his steak. She taught Mary to fill the ice bucket from eleven a.m. forward and to make sure the liquor cabinet always had enough booze. Mary fixed the squeak and slam of the kitchen door. She set up the ironing board permanently in her room, where she pulled the green shades down over nearly shut windows. My mother had instructed Mary to dress for duty from breakfast through dinner, except for two hours each after- noon and Thursdays and Sundays after lunch. During her time off, Mary often did the ironing. Occasionally she sat on the edge of her bed to read, sipping from a single orange soda poured over ice. My mother was delighted to find that Mary was a reader. A loan of a thick hardback, with a tall stone castle and a flowing- haired white maiden on the cover, soon waited on the bedside table beside Mary’s radio. “I wasn’t allowed to read those love books at home,” Mary remembers. “With my grandmother, I’d have to hide in the bed with a flashlight under the covers reading true confessions magazines. In Nantucket, as soon as your mother finished one of her books, she gave it to me. Learning all of that made me feel grown up. I didn’t bother her by wanting to go anywhere on my day off. I just wanted to be in my room reading. It worked for both of us.” On the hill where Mary grew up, whole families grew and were nurtured in a few small, low-ceilinged, well-kept rooms, in homes smaller than the one my parents called a beach “cottage.” In Nantucket, Mary encountered cabinets full of specialty foods, closets packed with store-bought clothes, a liquor cabinet bristling with bottles, and the diamond jewelry my mother wore each evening to dinner. Thinking about the immense class differences between our families, I asked Mary recently what de- tails she reported to her mother after that first summer. She told me, “I said, ‘Mommie, you should see all the pretty dresses and the perfume. And guess what, they eat lamb chops.’ When Mrs. C. asked me, ‘Mary, do you eat lamb chops?’ I thought I would die on the spot. I said, ‘No, Ma’am, we don’t eat that.’” Lamb was too pricey for her family, Mary says today, and, besides, she re- members her young aunt Dot saying that lambs cry like babies when they are slaughtered. Mary says that when she first saw the inside of my family’s house in Princeton that next fall, when she began going there weekly to do domestic work, she remembers “being in awe at all the beautiful things, the marble in the entrance, the high ceilings in the living room. I had only seen such things in magazines.” Mary noticed, also, the luxury of a family living together in a house large enough to hold them. Mary had lived most of her life in her grandmother’s home. Though her grandmother was solid and loving, Mary’s own mother lived as far away as ten miles without a car can be. My family could afford to live under the same roof. We could take a long vacation together. We could hire Mary to help make our vacation seamless and uncluttered, with no requirement to clean up after ourselves. I did not register for many years that our luxury was special, and rare, and required money that most families did not have. A later exchange Mary had with my mother revealed how little my family knew of Mary’s reality. She told me, “I remember a Friday a few years later in Princeton, when I said, ‘I am so glad today is payday because I was broke.’ Your mom said, ‘You have no money?’ At that time in my life, I didn’t have any money at all, not until I got paid. Your mom said, ‘How horrible! No money—I can’t imagine not having any.’ The look on her face was disbelief. I don’t think she could process such a notion.” The people Mary encountered in my family didn’t know material want, didn’t know self-reliance, didn’t know making do. One morning during Mary’s first week in Nantucket, I stood on the rickety wooden steps leading down to the beach. My mother was lounging in a beach chair, out on the sand where the dune grass ended, facing the ocean. Her long, tanned legs stretched out in front of her, glistening with oil; a silk scarf secured her blond hair against the breeze. To me, she looked glamorous, like a Hollywood star. Beyond her, swells lifted and set the green water in motion under the sunlight. In the cottage behind us, Mary vacuumed. All through my childhood, vacuuming was a comforting sound, signifying that someone was taking care of us and all was well. I flopped down next to my mother’s chair in the warm sand and sniffed the familiar perfume of her sun tan oil, the fresh mint in a tumbler of iced tea stuck in the sand nearby. “Finished the next Nancy Drew,” I whispered. She kept reading. When I couldn’t resist pulling at a string on the fraying edge of the chair’s canvas seat, my mother turned to me, her eyes hid- den behind big dark glasses. “This Nantucket experiment includes plenty of mother-daughter time . . .,” she began sharply, then stopped and changed her tone. “And we’ve been having it, haven’t we, sweetheart? We’ve had swims, and walks, and a shopping trip.” She took off her dark glasses to plead with me. “You’ll have a better time if you go meet some other twelve-year-olds. I’m sure there are loads of them just a five-minute walk away, all having a perfectly lovely time and not depending on their mothers. Your father will most definitely not like a lot of moping and heavy breathing in the offspring department.” The prospect of hunting for playmates made me crouch closer to my mother’s warm skin. As she returned to her place in the novel, the morning stretched before me, as long and as un- occupied as the empty beach. “Want to swim?” I said after a while. “I do not want to swim,” my mother said into her book. “This is my last chance at any peace around here. Tomorrow by the time I get my hair done, shop for groceries, and buy flowers for the table, it will be time to worry about your father’s airplane getting in. And then he’ll be here.” She stopped. “I mean, of course it will be lovely to have him.” From the dune behind us, we heard Mary call softly across the sand. “Can I freshen up your iced tea, Mrs. Coppedge?” My mother turned to smile at Mary, who stood at the top of the wooden stairs in a baggy white dress—the uniforms my mother had purchased drowned Mary’s slender body in shapeless white. “No more tea, thank you, Mary,” my mother said, “but you are very thoughtful. Why don’t you come on down to the water?” Mary held onto the splintery banister as if the steps threatened to float out to sea. “Have you been to the ocean before, Mary?” my mother asked. “Only on the ferry, Ma’am.” Mary took a step backward and squinted out at the expanse of moving green, letting her eyes go once, quickly, all the way to the eastern horizon. My mother laughed. “I hope you will come to love the ocean the way Wendy and I do.” Recalling this moment now, I realize that my mother assumed, based on her own experience, that Mary could swim. My mother also assumed that Mary would want, or feel free, to swim from a beach open only to wealthy white people. By now, I understand this viewpoint as white solipsism: We imagine that everyone shares our experience and our preferences. We fail to see beyond ourselves.3 By now, I know that learning to swim is a function of leisure and access—time to practice and a place to swim. Across the South during Mary’s youth, most public beaches and pools were closed to Black people. In our bubble of white solipsism, my mother and I did not consider that Mary might not have learned to swim. We had not learned about the Middle Passage, either—how generations of Africans had been kidnapped and transported by white shippers across the ocean to be enslaved in the U.S. and the Caribbean. We lacked a way to imagine that the embodied trauma of those crossings might still linger in a young African American woman’s apprehension of the sea. My father took a photograph on that Nantucket beach a few years later, during a summer when Mary’s first cousin, Linda Johnson, came in her place. In the photograph, Linda Johnson is in her early twenties. She stands uncomfortably on the sloped beach, squinting into bright sunshine. Her back is to the ocean. Her uniform stands out, glaringly white. I doubt that Linda John- son wanted her picture taken at that moment; she was working and not in her own clothes. Mary’s summer position—some- times passed along to her younger family members—might have been a decent job as domestic service went, but, from the perspective of time, Linda’s discomfort in front of my father’s camera suggests that posing for him in this way was a trying burden. My father pasted the photo into his scrapbook of Nan- tucket summers. Next to the photo, he wrote: “Linda Johnson does not like to swim.” I imagine he chuckled over the caption, thought his humor archly witty. Today I hear, not just a disparaging 3 In a powerful 1979 essay called “Disloyal to Civilization,” poet Adrienne Rich defined white solipsism in this useful way: “not the consciously held belief that one race is inherently superior to all others, but a tunnel-vision which simply does not see non-white experience or existence as precious or significant.” joke but the myopia of privilege. Dad seemed to assume that Linda could swim and was choosing not to. He ignored (or was ignorant of) the factors in Linda’s life that may have kept her from learning to swim. And, what if she did know how to swim? Exactly because Dad had succeeded so well in his goal of vacationing in an elite, white enclave, he must have known that Linda was not welcome to use the beach and water for her own pleasure. On that beach, Black people were tolerated only in glaring white service uniforms. Linda Johnson was not allowed to swim. A friend’s college-age son once worked a summer job at a Nantucket hotel. When I asked this young white man at the end of that summer how the island had struck him, he lifted tanned hands in the air, palms up. “White people swimming,” he said. He nailed Nantucket. White people in bathing suits strolled long, sandy beaches, refreshed themselves in the chilly Atlantic Ocean, and played in frothy surf that tumbled in from Portugal. A century earlier, a prosperous free community of Black whalers and sea captains had lived on Nantucket, owning homes, starting their own school, building businesses and a church, and leading the island’s abolition movement. After the whale oil market went bust in the mid-nineteenth century, many of the island’s Black residents left to seek opportunities elsewhere. Having lost the sources of income provided by the booming whaling industry, those who remained experienced increasing poverty and illness, and continued to suffer the racism of white Nantucketers. By the time that Mary came to Nantucket in the mid-twentieth century, Black and brown Nantucketers worked as maids, construction workers, and garbage collectors, while white people swam. My father’s photo and quip do not, in the end, tell anything about Linda Johnson, may she rest in peace. They speak of my father’s limits, and my mother’s, and mine, before I began to learn how much I didn’t know. On the private beaches of my youth, or in the Pretty Brook private pool in Princeton, I didn’t notice that I swam only with white people, let alone wonder why. As I consider this question today, I land, with a queasy feeling, on the pseudo-science of eugenics. Shortly before my birth, Hitler exploited eugenics to assert the supremacy of the Aryan “master” race over Jews, homosexuals, and Romani people—and to legitimize genocide. Eugenics in the United States has long fed the myth that Anglo- Saxon white people are genetically—and thus physically, mentally, and morally—superior to non-affluent immigrants and people of color. According to this lie and scare tactic, swimming in the same water as Black people threatened to make white people sick. Beneath this lie was fear of miscegenation. Health became a convenient rationale for exclusion. I say “convenient,” because, as Black medical sociologist Dorothy Roberts observes in her groundbreaking book, Fatal Invention: How Science, Politics and Business Recreate Race in the Twenty-First Century, eugenics has nothing to do with health: “In reality, eugenics enforced social judgments about race, class and gender cloaked in scientific terms.” The lies of eugenics featured in my own upbringing. My mother’s aristocratic mother used to refer to people from the lower classes—New York’s Irish and Italian immigrants, for ex- ample, and the Black people who came to the city from the South during early waves of the Great Migration—as “the great unwashed.” My grandmother wore gloves every time she left home and taught me to do so, as though there were dirty people out there from whose grime and germs I must protect myself. Within a week of Mary’s arrival in Nantucket, this became a new normal for my vacationing family: Mary in the kitchen, Mary making beds and vacuuming, Mary in her room at the ironing board, a sea breeze sucking and flapping the shades. Peeking discreetly through a slightly opened living room door to see what my mother needed, Mary entered the main part of the house only to clean or to bring or to take away. She performed her job so well—and so invisibly—that my mother quickly found her service to be indispensable. The work of sociologist Judith Rollins helps me understand more critically many aspects of my family’s relationship to Mary’s role that first summer, and helps my memory turn a sharper edge. Graduate of Howard University and Brandeis University, and recently retired as Professor of Africana Studies and Sociology at Wellesley College, Dr. Rollins began her career with a prize-winning 1985 study titled Between Women: Domestics and Their Employers. In her research for the book, she interviewed white employers and Black domestic workers in the Boston area and took several domestic jobs in white families, herself. This was in the 1980s, nearly thirty years after Mary’s arrival in my family’s summer kitchen, but the dynamics that Rollins writes about ring true. Take, for example, the way my parents warmed to Mary’s sweet willingness. Rollins says, “[T]o maneuver oneself into a satisfactory position—one not overly physically demanding, with more than minimal material benefits and with job security—one must have a pleasing personality as well as, if not more than, good housework skills.” Mary’s pleasing personality was absolutely necessary to her success in the job. When Rollins posed as a domestic worker for her research, she was stunned to find that members of the employers’ families talked, joked, even fought, in the same room where she was at work as if she was not present. They acted as though she were invisible, not present, not a human being. The deadly antecedents of this invisibility come clear to me in a contemporary poem by Terrance Hayes. In “Antebellum House Party,” Hayes conjures wooden furniture as a many-layered metaphor for the scandalous fact that plantation owners regarded, and treated, enslaved Africans as inhuman objects. “To make the servant in the corner unobjectionable / Furniture,” Hayes’s speaker begins, “we must first make her a bundle of tree parts / Axed and worked to confidence.” I recoil from the brutal image of a human being axed. I think, My family was not brutal like that. But being unobjectionable is exactly what my parents wanted from Mary. To succeed in domestic service, a person must axe away anything that might draw attention. The enslaver in Hayes’s poem wants his workers to be invisible. Furniture, he says, “Can stand so quietly in a room that the room appears empty.” My parents valued Mary’s invisibility, her gift for doing her work without drawing notice to herself. They would have said that they saw her as a human being, but they wanted her, like furniture, to be invisible. Hayes’s poem even foretells breakfast in my family’s rented beachside living room that summer: “Boss calls / For sugar and the furniture bears it sweetly.” I remember how often my parents praised Mary for being a “sweet girl,” and so willing. Her seamless invisibility made her work eminently satisfactory, her presence a guarantee of normalcy in the many summers to come. A century may have divided Mary’s service from the inhumanity of chattel slavery, but these haunting parallels reveal the institution of domestic service to be damningly unchanged. My father arrived on schedule from New York’s LaGuardia Air- port to Nantucket that first Friday evening. He visited briefly in the kitchen, looking tall and distinguished in his gray suit, his wavy brown forelock neatly combed and his intense gray-green eyes friendly. When he was introduced to the new member of our household, he spoke in the lilting, infantilizing tone he re- served for young children. “Mary White—what a nice, simple name for a pretty little colored girl,” he said. “Mrs. C. tells me you are doing a fine job.” His words could have landed with Mary as kind intention or clueless condescension—or both. The spatula shook in Mary’s hand the next day as she fried the corned beef hash and tomatoes for my father’s first lunch. She’d spent all morning getting ready. Three times she washed the hard, yellow plastic plates and cups and dried them with a fresh white dish towel. I thank Judith Rollins’s work for informing me that, though the woman of the house may give the instructions, the women who do domestic work always identify the real boss. As I remember Mary’s nervousness serving my father for the first time, I take her trembling hands as signs of a reasoned ap- prehension, a well-founded worry about pleasing him. I was playing solitaire at the kitchen table when my mother came out to say that the first lunch had been perfect. Next week- end, she said, she and my father would have a small dinner party on Saturday evening. Mary wiped and re-wiped the counter and said, “Yes, Mrs. Coppedge,” but she looked like she was going to worry until then. “I can help!” I said. “I trust that by next Saturday you’ll have plenty of friends to be busy with,” my mother said. “You should be out having fun,” Mary said. The two of them stood side by side, looking at me together, agreeing with each other about what I should be doing. For the next thirty years, the bond between Mary and my mother would both feature and exclude me, stirring my jealousy and troubling my ethics.Discussion Questions

What is a passage or moment in the book that stays in your mind?• Why is Wendy and Mary’s friendship unlikely? [or] What are some of the obstacles arrayed against Wendy and Mary’s becoming friends?

• What did Wendy have to learn in order to “see Mary more fully and become a more dependable friend?”

• What moments in the book showed Mary’s graciousness and patience with Wendy’s missteps coming through?

• Consider an interracial friendship in your life. Are there dynamics that you recognize from Mary and Wendy’s evolving relationship?

• This book is in part a grief memoir for Wendy’s mother; what other grief does the book evoke?

• What did you learn from Mary Norman’s experiences working in corrections? What does Mary’s humane approach to incarceration and rehabilitation reveal about the era of mass incarceration that began during her last years at the Correction Center?

Book Club Recommendations

Recommended to book clubs by 0 of 0 members.

Book Club HQ to over 90,000+ book clubs and ready to welcome yours.

Get free weekly updates on top club picks, book giveaways, author events and more