BKMT READING GUIDES

Areas of Fog

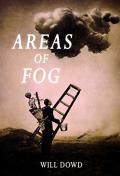

by Will Dowd

Paperback : 160 pages

1 club reading this now

0 members have read this book

Introduction

Will Dowd takes us on a whimsical journey through one year of New England weather in this engaging collection of essays. As unpredictable as its subject, Areas of Fog combines wit and poetry with humor and erudition. A fun, breezy, and discursive read, it is an intellectual game that exposes the artificiality of genres.

Will Dowd is a writer and artist based outside Boston. He earned an MFA in Creative Writing from New York University, as a Jacob K. Javits Fellowship; an MS from MIT, as a John Lyons Fellow; and a BA from Boston College, as a Presidential Scholar.

Excerpt

OVERTURE All the weathermen of New England go mad eventually. After a few decades spent attempting to predict the unpredictable, they succumb to a kind of meteorological nihilism and wander out of the studio mid-broadcast, muttering to themselves, and can be seen a week later selling wilted roses on the side of the highway. It’s not the seasonal anarchy—all those balmy Christmases and washed-out Junes—but rather the perverse changeability of our daily weather, the adolescent moodiness of our sun and sky, that finally unravels the sweater of their sanity. “In the spring, I have counted one hundred and thirty-six different kinds of weather inside of four and twenty hours,” Mark Twain, a Hartford resident for seventeen years, once quipped. Yet while they may be doomed to fail, we don’t mock our weathermen. Even though we see them for what they are—oracles draped in sheep entrails—we don’t change the channel. We listen politely to their forecast. And then we talk about it. In New England, the weather is all we talk about, especially when we have nothing to talk about. Lately, I’ve been suffering from writer’s block. It’s a serious disease. It struck Twain in the midst of composing The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. After scratching 400 handwritten pages over the course of a single summer, the author suddenly found he could not write another word. For years, Huck and Jim were left stranded on the river, paddling in place. Eventually, Twain found his cure: a refreshing 16-month trip through Europe. I’m hoping to find my cure closer to home. Over the next year, I plan to keep a weather journal, a kind of running retrospective forecast. It will be accurate, for one thing. I can say it rained today with 100% certainty, for example, because I swallowed some of it. But I have another reason for glancing at the near meteorological past. Writers only ever use the atmosphere for atmosphere. They never give the weather its literary due. “Of course weather is necessary to a narrative of human experience,” Twain wrote. “But it ought to be put where it will not be in the way; where it will not interrupt the flow of the narrative.” So here’s a place just for the weather: a snow globe without a figurine or a monument. Just the weather. And maybe, probably, my reflection in the glass. ? January ? LONDON TOWN Nothing was happening this week, weather-wise. Monday was mild—a fugitive March day hiding out in mid-January—while Tuesday left so little impression on my mind that I could not swear in a court of law the day actually transpired. Then the fog rolled in. It happened on Wednesday night, when no one was looking. Dusk fell, the mercury dropped, and suddenly the whole east coast of Massachusetts was saturated in abject eeriness. I walked outside and found reality suspended, the everyday world dissolved in a cataract gloom. Somewhere ahead of me in the white murk, I heard the hollow sound of a glass bottle rolling on its side. It came to a jangling stop against a curb, then began rolling again, back the way it had come. All considered, the fog gave me the haunting sense that strange things were about to happen. I felt like a character on the first page of a novel. I wasn’t alone. “I feel like we’re in Sherlock Holmes,” my grandmother remarked when I saw her on Thursday. She was right, of course. It was fine weather for fishing a body from the Thames or swinging your cane at a street urchin. If anyone recognized the literary merits of fog, it was the Victorian authors, who practically mass-produced the stuff. It was their way of dropping a veil on their hyper-rational, industrialized metropolis. In one Sherlock Holmes story, the bored detective condemns London criminals for not taking advantage of a weeklong fog. “The thief or the murderer could roam London on such a day as the tiger does the jungle,” Holmes says. “It is fortunate for this community that I am not a criminal.” Interestingly, at least to an English major, fog always seems to gather on the first page of these stories. It pours through Scrooge’s keyhole at the start of A Christmas Carol, swirls with metaphoric import at the beginning of Bleak House, and even appears in its cousin form—marsh-mist—to blind Pip at the dawn of Great Expectations. And that’s just Dickens. Fog belongs on the first page of novels. That’s how literature comes to us. It emerges from the ghostly haze of the blank page, and if you take just a few steps into it, you lose sight of who you were and where you came from. Take Sherlock’s advice to Watson: bring a revolver.? BARE BONES It’s always this time of year—when the snowstorms have begun to bleed into each other and the air, just teething in December, now has real bite—that my pale Irish skin loses its ivory sheen and becomes actually translucent, and you can see my major organs quivering like koi fish under a layer of ice. It was a week of slow, steady accumulation. On Saturday, we had snowflakes the size of movie tickets. On Wednesday, they flew in our eyes like flicked ash. By Friday, every window in New England was like the frame of an Andrew Wyeth winter landscape. Andrew Wyeth loved this time of year. The painter, who died five years ago this week, spent most of his life on long walks with his paper and sable brushes, trying to find the right snowbank to sit on. “God, I’ve frozen my ass off painting snow scenes!” he once supposedly said. It’s one thing to be a plein-air artist in the south of France, but anyone who shoveled their driveway this week has to respect a man who painted mittenless in this weather for decades. For Wyeth, exposure to the elements was essential to his art. It got him out of his head. “When I'm alone in the woods, across these fields, I forget all about myself, I don't exist,” he said. “I'd just as soon walk around with no clothes on.” I used to think Wyeth chose his favorite subject—isolated barn in a sea of snow—mostly to save paint. Some of his finished watercolors are more than seventy percent untouched paper. But the more I look at his wintry landscapes, the more they seem to take on an otherworldly glow. For Wyeth, the white space of winter was not a shortcut. It was a mystery. “I prefer winter and fall, when you can feel the bone structure in the landscape—the loneliness of it,” the painter said. “Something waits beneath it—the whole story doesn’t show.” This is especially true for “Snow Birds,” a Wyeth watercolor recently slated to be auctioned at Christie’s for $500,000. Shortly before being sold, it was discovered to be a fake. (You can always expect a flurry of forgeries in the wake of an artist’s death.) There are small details that give it away. For example, Wyeth painted pine trees by laying down an undercoat of green, then trickling black branches over it—not the reverse, as seen in the fraud. Also, the forger was too stiff in his brushwork. The shadows are labored; the hillside is stilted; even the signature is too neat. Wyeth, who painted with fingers that ached to be back in his warm pockets, was all speed and dash with his brushes. No, this winter landscape was not painted by Andrew Wyeth. It was not painted by someone whose hands were cold.Discussion Questions

1. “London Town” is the opening essay. In this piece, Will Dowd discusses the literary merits of fog. What other stories can you think of which prominently feature fog?2. In “Latitudes,” Dowd asks “Why do I live here?” Was there ever a time when you felt the same way about where you live? Has weather ever ruined an event for you?

3. “Bare Bones” discusses the painter Andrew Wyeth and the number of forgeries that arose after his death. What do you think Will Dowd meant when he said the forgery of “Snow Birds” was not painted by someone “whose hands were cold”?

4. In “Beach Walk,” do you agree with Dowd’s statement, “To sit on a seawall and stare morosely into the ocean is one of life’s great pleasures”? Can you remember the last time you sat near the ocean? Is it just the ocean that allows you to cast a line of thoughts? Would a lake or river suffice as well?

5. In “Rara Avis,” Dowd recounts a late-night encounter with a black kitten and jokes that he sometimes suspects sparrows are talking about him. When was your last encounter with an animal in nature?

6. Consider the phrase, “Carpe Diem.” Dowd claims we don’t seize the day, the day seizes us. Do you agree or disagree?

Choose a selection that resonated with you. Discuss why it had such an impact on you.

7. Discuss examples of how Dowd uses personification when describing the weather.

8. The titles of the essays all relate in some way to a famous historical person or literary work. These references are often subtle and may take a bit of digging to uncover the treasure. Consider some of the titles and discuss their correlation to the content of the essays.

9. Dowd mentions various people from history who harbored deep secrets. Choose one of these famous people and discuss how the secret helped or hindered his or her success.

10. Dowd uses comedy to balance the sometimes serious nature of weather. Choose an essay that combines seriousness with humor. What makes the opposing elements work in your chosen essay?

11. Discuss the essays that touch upon human frailty. How does Dowd convey his message?

The titles of the essays all relate to a person or literary work in some way. These references are often subtle and may take a bit of digging to uncover the treasure. Choose four titles (one from each season) and discuss the correlation of the title to the content of the essay.

12. The essay “An Inner Scheme” includes an actual inner scheme, a literary code that involves Vladimir Nabokov. Were you able to figure out Dowd’s secret message? (If you’re stuck, consider what Nabokov told his editor.)

13. In “The Silent W,” Dowd discusses nomen est omen, the concept that our name is our destiny. Do you agree with this idea?

14. In “The Painter of Sunflowers” and “High and Dry,” how is the sun depicted differently?

15. Do you agree with Dowd that The Great Gatsby and other classic works of literature change as you age?

16. Discuss three examples of imagery that stuck with you.

17. In the “Outro,” Will Dowd includes a haiku from the poet Issa. Do you think the poem was an appropriate way to end the book? Would you agree the fog of his writer’s block has lifted?

18. The cover image for Areas of Fog is titled “Cloud Cleaner.” How does this resonate with the lyrical nature of the essays?

Suggested by Members

Book Club Recommendations

Recommended to book clubs by 1 of 1 members.

Book Club HQ to over 90,000+ book clubs and ready to welcome yours.

Get free weekly updates on top club picks, book giveaways, author events and more