BKMT READING GUIDES

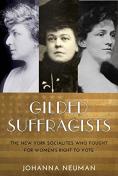

Gilded Suffragists: The New York Socialites who Fought for Women's Right to Vote

by Johanna Neuman

Published: 2017-09-05

Hardcover : 240 pages

Hardcover : 240 pages

1 member reading this now

1 club reading this now

0 members have read this book

1 club reading this now

0 members have read this book

New York City’s elite women who turned a feminist cause into a fashionable revolution In the early twentieth century over two hundred of New York's most glamorous socialites joined the suffrage movement. Their names—Astor, Belmont, Rockefeller, Tiffany, Vanderbilt, Whitney and ...

No other editions available.

Jump to

Introduction

New York City’s elite women who turned a feminist cause into

a fashionable revolution

In the early twentieth century over two hundred of New York's most glamorous socialites joined the suffrage movement. Their names—Astor, Belmont, Rockefeller, Tiffany, Vanderbilt, Whitney and the like—carried enormous public value. These women were the media darlings of their day because of the extravagance of their costume balls and the opulence of the French couture clothes, and they leveraged their social celebrity for political power, turning women's right to vote into a fashionable cause.

Although they were dismissed by critics as bored socialites “trying on suffrage as they might the latest couture designs from Paris,” these gilded suffragists were at the epicenter of the great reforms known collectively as the Progressive Era. From championing education for women, to pursuing careers, and advocating for the end of marriage, these women were engaged with the swirl of change that swept through the streets of New York City.

Johanna Neuman restores these women to their rightful place in the story of women’s suffrage. Understanding the need for popular approval for any social change, these socialites used their wealth, power, social connections and style to excite mainstream interest and to diffuse resistance to the cause. In the end, as Neuman says, when change was in the air, these women helped push women’s suffrage over the finish line.

Excerpt

“A great many people fear that giving a woman her honest equal rights in the world’s work is bound to make her act mannish. … My experience is that so far as it has been tried out it merely makes her act a little more like a gentleman.” — Raymond Brown CHAPTER 6: MERE MEN Business stopped in Rhinebeck, New York the day Jack Astor was buried. The quaint town in Dutchess County, home of Ferncliff, the Astor estate, lowered its flags to half-mast. Bells tolled at noon, and residents crowded the train station as his body was placed on board for the trip to Manhattan. There, at Trinity Cemetery on Washington Heights, the 47-year-old scion of real estate wealth and social prominence was laid to rest in the family vault next to his mother, the indomitable Caroline Schermerhorn Astor. Outside the cemetery, thousands perched near walls and on the fence and “on either side of Broadway and 155th Street, while others sought the roofs of adjoining apartment houses, and the viaduct along the river overlooking the burial ground,” to catch a glimpse of this man of gallantry, who “went to his death nobly,” a man who had “died to let woman live.” When the RMS Titanic went down on April 12, 1912, it took more than fifteen hundred passengers to their frigid death, many victims of hypothermia in 31-degree water that shut down their organs and rendered them unconscious in minutes. It made a hero of John Jacob Astor IV, a sportsman who had hardly been that in life. And it sparked a nationwide debate over chivalry, that unwritten law of the sea — the call of “women and children first” that prompted Astor and other men to forfeit seats on lifeboats for female passengers. If men had protected women from death, should women enjoy rights of citizenship in life? Critics said no, chiding suffragists for their audacity – some said hypocrisy — in seeking equality at the ballot box when men had just made the ultimate sacrifice at sea. “Let the suffragists remember this,” argued one letter-writer to the Baltimore Sun. “When the Lord created woman and placed her under the protection of man, he had her well provided for. The Titanic disaster proved it very plainly.” In an editorial, the Sun’s editors agreed, arguing that women did not need the ballot. As the Titanic episode demonstrated, “women can appeal to a higher law than that of the ballot for justice, consideration and protection.” Identifying himself as “Mere Man,” another wrote in telling sarcasm, “Would the suffragette have stood on that deck for women's rights or for women's privileges?” The question hung over the movement in New York as suffrage leaders planned a street parade “the like of which New York never knew before.” Moved by the nobility of the men who perished, some urged a postponement. “After the superb unselfishness and heroism of the men on the Titanic, your march is untimely and pathetically unwise,” anti-suffragist Annie Nathan Meyer, founder of Barnard College for Women, wrote to organizers. Even some who planned to march wished men had not forfeited their lives for the lofty code of chivalry. “The women should have insisted that the boats be filled with an equal number of men,” observed suffragist Lida Stokes Adams. For others, the tragedy only bolstered the case for giving women a vote, and a voice, in politics and commerce. Had women been involved in planning, they argued, the Titanic, driven by male ego and a conviction that the ship was unsinkable, might have been equipped with a sufficient number of lifeboats for all the passengers, negating the need for chivalry. “There was no need that a single life should have been lost upon the Titanic,” wrote Alice Stone Blackwell. “There will be far fewer lost by preventable accidents, either on land or sea, when the mothers of men have the right to vote.” Invoking the cloak of motherhood, Blackwell and others lobbied for the vote on grounds of moral probity, sure a female presence in the political world would “bring humaneness, the valuation of human life, into the commerce and transportation and business of the world.” As for chivalry, muckraker Rheta Childe Dorr expressed the cynicism of many when she wrote of conditions at one Brooklyn sweatshop, where locked doors and bad odors imprisoned workers. “The law of the sea, women and children first,” she said. “The law of the land – that’s different.” Only hours after Jack Astor was buried, some 20,000 suffragists marched down Fifth Avenue in an exuberant affirmation of their rights as citizens. In response to the male chivalry represented by the Titanic’s fateful ending, suffragists offered female discipline. Parade organizer Harriot Stanton Blatch banned automobiles, believing they shielded wealthy or lazy activists from the chore of actually walking – or of having been seen walking — for suffrage. “Riding in a car did not demonstrate courage. It did not show discipline,” Blatch wrote later. “Women were to march on their own two feet out on the streets of America's greatest city; they were to march year by year, better and better.” They were to dress in white – Macy’s was the official headquarters for suffrage paraphernalia – and march in step with one another, column after column of women, “a mass of gleaming white,” declaring their interest in the ballot. Eager to defuse criticism that women had dallied the previous year, evidence of their unsuitability for the ballot, Blatch insisted the 1912 parade began promptly at 5 p.m. “Eyes to the front,” read her orders, “head erect and shoulders back,” and above all, remember that “the public will judge, illogically of course, but no less strictly, your qualification as a voter by your promptness.” Vowing to feminize the concept of the street parade – with its male overtones of military combat – she concluded, “Men and women are moved by seeing marching groups of people and by hearing music far more than by listening to the most careful argument.” But what most fascinated press and public was the decision of an estimated one thousand men to join in the parade. The previous year, eighty-seven men had shown up for a women’s suffrage parade, enduring great derision from sidewalk hecklers. Now, three weeks after the sinking of the Titanic that had ripped bare the false virtue of chivalry, they marched in rows of four across, under the wind-swept blue banner of the new Men’s League for Woman Suffrage. “As if to give courage to the less courageous of the mere men marchers,” reported the Times, a band “broke into a lusty marching tune as the men swung from Thirteenth Street into Fifth Avenue.” Perhaps they could still hear the jeers through the drumbeat: “Tramp, tramp, tramp, the girls are marching.”Discussion Questions

What role do you think celebrities played in the campaign by women to win the right to vote?Do you think it was moderates who lobbied Congress or militants who picketed the White House who most helped the cause?

Why do you think social changes takes so long to achieve?

Book Club Recommendations

Recommended to book clubs by 0 of 0 members.

MEMBER LOGIN

BECOME A MEMBER it's free

Book Club HQ to over 90,000+ book clubs and ready to welcome yours.

SEARCH OUR READING GUIDES

Search

FEATURED EVENTS

PAST AUTHOR CHATS

JOIN OUR MAILING LIST

Get free weekly updates on top club picks, book giveaways, author events and more

Get free weekly updates on top club picks, book giveaways, author events and more

Please wait...