BKMT READING GUIDES

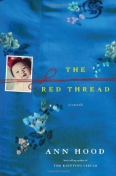

The Red Thread: A Novel

by Ann Hood

Hardcover : 304 pages

14 clubs reading this now

8 members have read this book

After losing her infant daughter ...

Introduction

From the best-selling author of The Knitting Circle, a mother's powerful journey from loss to love. In China there is a belief that people who are destined to be together are connected by an invisible red thread. Who is at the end of your red thread?

After losing her infant daughter in a freak accident, Maya Lange opens The Red Thread, an adoption agency that specializes in placing baby girls from China with American families. Maya finds some comfort in her work, until a group of six couples share their personal stories of their desire for a child. Their painful and courageous journey toward adoption forces her to confront the lost daughter of her past. Brilliantly braiding together the stories of Chinese birth mothers who give up their daughters, Ann Hood writes a moving and beautifully told novel of fate and the red thread that binds these characters? lives. Heartrending and wise, The Red Thread is a stirring portrait of unforgettable love and yearning for a baby.

Excerpt

There exists a silken red thread of destiny. It is said that this magical cord may tangle or stretch but never break. When a child is born, that invisible red thread connects the child’s soul to all the people—past, present and future—who will play a part in that child’s life. Over time, that thread shortens and tightens, bringing closer and closer those people who are fated to be together.Hunan, China WANG CHUN “Who will get this baby?” Wang Chun asks out loud. “Who will take her in and cherish her?” She lifts her baby daughter to her breast and guides the nipple to the child’s mouth. This baby is slow to suck, as if she knows her fate. Chun wills herself to keep such thoughts from her mind. It is all yuan, destiny. To think of her daughter’s fate will not change it. Hadn’t her mother told her, “The sky does not make dead-end streets for people”? Hadn’t her husband said when the first pains began just five days ago, “Remember, Chun, we can have many more babies if we must”? Hadn’t he told her this morning as she set out from their home with this baby in the sling, bouncing gently against Chun’s hip and still-swollen stomach, “Remember, Chun, a girl is like water you pour out”? And hadn’t she nodded when he said this, as if she agreed with him, as if she too believed a daughter was just water that you poured out and let flow away? The child’s sucking is lackluster and weak, and for an instant Chun’s heart lifts. Perhaps this baby is sickly. Perhaps her weak sucking is a sign that she would not live long. Chun almost smiles at the idea. If she is going to lose her daughter anyway, wouldn’t it be easier now at only five days old than later, at five months or even five years? But then, as if the baby reads Chun’s thoughts, she latches onto the nipple hard and begins to suck noisily, voraciously. The baby lifts her eyes toward Chun, eyes that until this moment have not focused on anything at all. Instead, they have been cloudy and half shut, like a kitten’s. Now the baby settles her solemn gaze right on Chun’s face and sucks the milk from her breast hard as if to say, No, Mother! I am here to stay! Chun wants to look away, but she cannot. Their eyes—mother’s and daughter’s—stay locked until the baby has her fill. She hiccups softly, then lets her jaw go slack without dropping the nipple completely. It seems she does not want to let go. “You must,” Chun says softly. “You must let go.” She intends these words for her infant daughter. But somehow she seems to be speaking them to herself. The sun is setting, turning the sky a beautiful lavender, the clouds violet and magenta and gray-blue. Chun has not allowed herself to call this baby anything. But now she leans forward to kiss the top of her daughter’s head, and as she does so she whispers, “Xia”—colorful clouds. Then Chun takes the now-sleeping baby and settles her into the basket. She places the cotton blanket over her snugly, being sure to tuck it in tight. The basket is of a type particular to her village. Someone who knows her village, who has traveled the seven hours down the back roads, past fields of kale, would recognize this basket. They would see this sleeping baby in this particular basket and know where she had come from. The blanket too might provide a clue. It is made of pieces of Chun’s own clothing, with fabric bought in the village. The purple and navy blue cotton had been her own pants and tunic. She cut them carefully into squares and sewed those squares together the day after the baby was born, knowing what she would have to do. But a person who had visited her village might be able to say that this fabric came from there. Chun chides herself for her sentimentality. It is a bad idea to leave clues. Her very own neighbor was recently caught leaving an infant daughter in this very city where Chun now stands staring down at Xia. This neighbor brought the baby right up to the door of the social institution, leaving her in a box that had held melons sold in the village market. She had placed the baby there at sunrise, then stood half hidden behind cars parked in the yard. When the head of the institution arrived for work, she saw the woman there and said sternly, “You! What are you doing in this yard?” Of course the neighbor tried to run, but either fear or guilt kept her there, frozen to that spot behind the cars, crouched and trembling. “You do know that I am legally obliged to call the police if you have left something here?” the woman said. Her eyes darted to the doorway where the box sat with the baby inside. “Is that yours?” the woman said, her voice kinder now. “I will turn around, and when I look in your direction again, you and your belongings should be gone.” The woman did just that. She turned around and waited several minutes. Chun’s neighbor ran to the door and took her daughter from the box that had held melons and fled that yard. When she returned home later that day, dusty and hungry, with the baby in her arms, her husband slapped her so hard that she fell to the floor. What else could he do? Chun’s husband asked her when she told him this story which the neighbor herself had told Chun. And Chun had answered, Nothing. There was nothing else he could do. She did not tell her husband the rest of the story, how the neighbor’s husband had taken the baby from her, and set off down the road that led out of the village himself. He left instructions for his parents to not let his wife back in the house until he returned. Luckily it was summer, and the woman slept in the garden and ate the radishes that grew there. Her breasts began to leak milk, and to grow hard and painful from the need to nurse her daughter. Inside, her older daughter peered from the window, curious about her mother sitting alone in the dirt with large wet circles spreading across her cotton dress. But the child was too young to ask questions or to help her mother, who began to wail as time passed and her breasts ached and overflowed and her husband did not return. That night she slept outside in the dirt, and the next day she ate radishes for breakfast, and then, out of her mind from pain and grief, she unbuttoned her dress and squeezed the milk from her breasts even though she saw her mother-in-law staring at her. Her lip where her husband had hit her felt swollen and she could still taste the iron of her blood there. And she bled from her recent childbirth so that the inside of her legs felt sticky. Her breasts could not seem to empty of their milk and ached even more. When her husband came home empty-handed that afternoon, he did not let her in. He did not even make eye contact with her. He simply ignored her. The sounds of her husband and their daughter and her in-laws making dinner and eating together, the smells of ginger and hot pepper, all of it assaulted her. She called to them to let her in, to give her food. But it wasn’t until the next day that he appeared at the door and motioned her inside. What have we learned from this? Chun’s husband had asked her. She shook her head. Number one, he said: Leave the child when it is dark. Number two: Walk away. Number three: Do not go to the institution. Number four, Chun said. Number four? her husband asked, confused. Number four, Chun said, do not love the child. DARKNESS HAS FALLEN. It is time. Chun lifts the basket carefully so as not to wake Xia. She emerges from the cluster of trees at the edge of the park and walks across the grass, past the abundant flowers, to the pavilion. Tomorrow is the first day of the Flower Festival and this now-empty park will be filled with people. Someone is sure to find this basket from the distant village with the baby girl inside it, and when they see the precious gift there that person will surely take Xia to the appropriate place. She has been told not to wait to be certain this happens. Her husband has warned her to walk away. But the night is so dark and the basket looks so small, like a toy, that Chun finds she cannot leave. She stands in the dark, silent park, hesitating. Would it be so terrible to go back to that cluster of trees and wait there? From that place she can see the pavilion. She will be able to see a person emerge with the basket that holds Xia. She will not have to tell her husband that she has done this. She can simply say that the long walk made her weary and that she slept a long time before heading back home. Satisfied with her plan, Chun walks back past the flowers, across the grass, to the cluster of trees. She takes the sling that had just a few hours ago held her newborn daughter and rolls it up like a pillow to put beneath her head. As she looks upward, the leaves make a pattern like lace against the sky. Chun stares at this pattern and thinks of how she does not want to make this journey again. Last year she had a daughter whom she left at the police station of a different city. The year before she had a daughter whom her husband had agreed, reluctantly, to keep. She does not want her heart broken again. How many daughters can a woman lose and still love her husband? Still cook dinner and grow vegetables and smile at others? Her heart is broken into so many pieces already. One daughter who knows where? One daughter in a basket across the park waiting for someone to find her. Yet even today, only five days after this child was born, her husband had smiled at her and said, Hurry back, and Chun had known he meant hurry back so that we can try again for a son. But Chun feels certain that she was made to only have daughters. She stares up at the leaves and considers her dilemma. Can a woman turn her own husband away in bed? Can she deny him his needs, his longing, his son? Chun has no answers. She knows only this: She cannot abandon another baby. Her eyelids grow heavy and her mind goes where she does not want it to go. Last year, when she left her three-day-old daughter on the steps of the police station, it was January and cold. What Chun fears is that despite the layers of clothing, despite the blankets she’d so carefully swaddled the baby in, despite her pleading with the heavens to protect her baby, the child did not get found in time and froze to death in the winter night. The thought jolts her awake. Chun sits up, her heart beating hard. Even though it is not quite dawn, trucks are pulling into the park. Chun stumbles to her feet. Her mouth is dry and foul-tasting. Her breasts are heavy with milk. She puts her hand to her chest as if that small gesture can stop the pounding of her heart. Men in orange work clothes emerge from the trucks and begin unloading chairs, swaths of cloth, equipment of some kind. They move toward the pavilion, their figures slowly illuminated in the rising sun. Then Chun hears the sound of excited voices. One of the men lifts her basket high, like he has won a prize, and hands it down to the men. Xia is lost in a blur of orange. Chun waits, unsure of what to do. Then she turns from the park and walks north, toward home, with quick determined steps. “Who will get this baby?” Wang Chun asks out loud. “Who will take her in and cherish her?” Of course, she has no answers. Only a mother can love a baby the right way. Only a mother truly cherishes her children. Something in her wants to go back and shout: That is my daughter! But Wang Chun keeps moving steadily away.

Discussion Questions

1. Describe how each of the characters reacts to the idea of adoption. How are they similar? What makes them different?2. How does Maya deal with the loss of her daughter? How does her reaction affect her relationships with and opinions of others?

3. How does Maya’s confession to Jack change her interactions with the people around her, particularly her coworkers?

4. Flowers are a prominent motif throughout THE RED THREAD. Discuss the significance of this.

5. Many of the characters have habits that help them cope through tough situations. How do these habits help or hinder them?

6. Compare and contrast the American couples to their Chinese counterparts.

7. A red thread is said to connect mother to child. Do you think there is also a connection between the expectant mothers at The Red Thread Agency?

8. What do you think about Brooke’s decision? How do you think this decision will affect her in the future?

Does it change the way you view the rest of the characters?

9. Compare and contrast the babies’ Chinese names and their new American ones. How do the names fulfill the hopes and dreams of the mothers, both Chinese and American?

10. How do you think the new parents will deal with the ethnic differences between themselves and their children? What types of things should they do to integrate themselves with their child’s Chinese heritage?

11. What do you think will happen to each of the couples after the novel ends?

Weblinks

| » |

Publisher's Book Info

|

| » |

Author Ann Hood's web site

|

| » |

Book Review from Publisher's Weekly

|

| » |

Book Review from Library Journal

|

Notes From the Author to the Bookclub

Note from the Author: In 2005, my family adopted a baby girl from China. Three years earlier, our five year old daughter Grace had died suddenly from a virulent form of strep, and in the grief that engulfed us my husband Lorne, our then nine year old son Sam, and I wanted to bring hope and joy back into our home. As we went through the adoption process, we heard so many moving stories of why people choose to adopt, as well as the impact that the one child policy has on families in China who are not allowed to keep their daughters. I wanted to write a book that told human stories of love and hope, disappointment and fear as we seek to have a child. Our own daughter, Annabelle, was five months old when she was found abandoned in a box at the orphanage door in Loudi in Hunan Province. These babies virtually have no history. But from the stories I heard--and from my own writer's imagination--I played out various histories in the form of the stories of the Chinese mothers in THE RED THREAD.Book Club Recommendations

Recommended to book clubs by 12 of 12 members.

Book Club HQ to over 90,000+ book clubs and ready to welcome yours.

Get free weekly updates on top club picks, book giveaways, author events and more