BKMT READING GUIDES

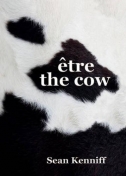

Etre the Cow

by Dr. Kenniff

Hardcover : 135 pages

2 clubs reading this now

1 member has read this book

Introduction

Humiliated by his hoofed legs, the flies on his haunches, and the grass in his mouth, a bull named Etre tells his tender and thought-provoking story about the brutal insignificance of cow life at Gorwell Farm. In a world where the line between disgrace and dignity is drawn by a pasture fence, Etre finds himself alone in his awareness and utterly powerless to change his circumstances. The farmer and his men control everything--herding the cows from pasture to pasture, raising the sun in the morning, and taking it down at night. Etre searches for understanding among the broads, bulls, and calves on the pasture, but finds none. On the best of days, Etre listens to the farmer's boy sing lullabies at the fence. He likes those songs and loves the boy. But the grasses thin as the seasons pass, the cows hunger, and Etre grows desperate. He is the only cow truly starving.

Excerpt

chaptêr one “Moo!” This happens so often I rarely take notice. Girls and men, boys and women call out to me, and to every one of us here, from outside this fence of wire and wood confining my pasture. “Moo, cow!” they shout, and I try not to turn. But I do, and as always, I am humiliated. They call out to my hoofed legs, the flies on my haunches, and the grass in my mouth. They cry at my stinking cowness. I am a bull, not a cow. But I am a beast and so are the others, and the shame of this burns like the sunshine on my back. It’s more crowded than ever on the pasture, and I can’t count us all—a few brutes, perhaps a few hundred broads and their calves. All the good grasses been chewed long ago and now we have only yellowed patches to fill our bellies. I haven’t eaten a daffodil in several seasons. When the rain comes, brilliant green sprouts burst through puddles and dung and dirt but are quickly trampled by the curious and careless. None of us here are patient. The men on the horses with their grinning dogs will soon come and move us all to better land, and we will eat without rest. If they don’t move us, we’ll starve. And if we starve, they starve, that’s my understanding of things. So I wait, with the others. They call this place Gorwell Farm, and I call myself être. It’s the only word I can say. I don’t reckon they say. But I do reckon. I’m not sure how long I’ve been doing that. It’s hard for me to tell. It’s like a cocoon just splits open one summer, a butterfly beats its wings and zigzags away. To the butterfly, the caterpillar never really figures. That’s how it happens, I think. “Unghf,” I say and swallow the blades on my tongue. “Unghf,” a nearby bull answers. “Anghf,” a cow says. The ants are on the move again, snaking their way through the grass in a jagged line. They pay me no notice even as I loom above them. In one direction most are hauling tiny bits of world in their pincers—leaves, insect wings, rotting pulp of apricot, and globs of mud. I follow one of them. He cuts under the thickets, over sticks, and in and out of cow tracks, holding a mantis head in his jaws. The mantis eyes look at me and I look away. I’m careful where I step when I follow. The ant disappears, and I push blades of grass out of the way with my face so he does not get lost to me. Along the path, ants crawling in the other direction meet this one, touch him, flail their antennae, and then move on. I nudge two sluggish broads with dim eyes out of the way; they are slow to move. I find my ant again. In the clearing he crawls faster and straighter. And when he finally arrives at his home, he drops out of sight down the hole. I wait. Then I decide to stop waiting, and I plough one of my hooves through his mound. This gets all the ants excited. They storm up my legs, bite at my flesh, and taste my enormity. To them I am incomprehensible, and after a while they leave me be. “Unghf,” I say, and pull roots from the dirt. Many in the herd are moving to the water at the long end of the pasture, where side by side they’ll gulp from the stream until they are fat and slow. On hotter days some will even stand in it. Water looks more interesting when a cow is standing in it. And I like to look at that. But this day it’s not that hot. I don’t much like going to the stream ever since my first time. I was smaller then, and I recall I got there just like the others—I followed. I slipped and crouched and bent my way between hundreds of cows, and then stretched my neck long until I reached the water’s edge. But my legs buckled. Under the water the most awful beast eyed me like it had been waiting for me all along; this hideous water-cow. “Mneweh,” I turned to the others, using a cry only calves can cry. For certain, the others had seen the water-cow. But they stood calm. So I crept back to the water’s edge and peaked in again. I didn’t go so far as to see its horrible face, but when I saw those ragged ears flickering on the surface, I thrashed my body backward. I turned, pushing and twisting my way between so many cows, and I ran from the stream until my legs folded. Later, when the other cows lumbered back to the pasture one by one, I walked back to the stream alone and again the water-cow was waiting for me. He had a rotten-apple nose, black and wet. Ears like mangled leaves. Two bird-egg eyeballs low on his head jutting from the sides of the skull. His hide was clay colored, not the rusty brown, black, or white I’d seen on the other cows, just the color of water-meets-earth. Like me the water-cow was a bull, or turning into one, with stubs for horns. His tongue, brown and thick and mottled, hung limply out of the side of his mouth. I moved my head this way, then that way, then this way again, and so did the water-cow. I snorted and so did the water-cow. His ears flicked. So did mine. I dipped my face into the water; he poked his face out. Our noses touched. “Unghf,” I bellowed, and so did he. I was this water-cow, he was me, and we were gruesome. As a calf, I would hide my face against my mother’s milky belly. But without her there is no hiding me. I’m a horrible cow, it’s true, the ugliest bull on the pasture, and I prefer to do my drinking at puddles of fallen rainwater. They bring the sun up, heating the other cows from their sleep. All night I walked among the heaving bodies until my thoughts lost shape in the light, having gone where the moon goes. I rest against a fence post and rub my hide until it stings. A door closes at the barn with a creak and clank. Farmer Creely is walking his boy and his dog. The boy is kind and I don’t much mind Farmer Creely. But that dog, I hate. Never met a dog I liked. Most of them not even as high as my belly but they chase us into big groups, snarling and nipping at us even as we run. Cows and bulls can’t outrun dogs. They’re there, then here, then there, then wherever we turn, and some days they taunt us without mercy. There are no bulls on the pasture when those dogs are around; we’re all cows then. The farmer and his dog walk down the trail on the side of the road, leaving the boy by a post at the fence. I walk near. “Jacques,” the farmer says, “you comin’ with?” “No, can I stay here ’n look at the cows?” “Suit yerself. But lookin’ don’t make a farmer now. Does it?” “No, Paw.” “Doin’ does, Jacques. Doin’ makes a farmer.” “I know, Paw,” the boy says. “We got to feed the pigs first, Jacques,” the farmer says. “Pigs come first.” “Uh huh.” “Now you stay right there while I tend the hog feed.” “’K, Paw.” “Don’t go off now, y’hear?” “I won’t, Paw.” “Right then.” “Right, Paw.” The farmer lifts a stick from the side of the trail and throws it high and far. The dog runs after it like it’s got no mind. I go close. “être,” I say to the boy. “Shoo, cow,” he says, rattling the fence, “yah, shoo!” and tosses a few stones against me. He must be thinking I’m one of the other cows, but I shoo away a little on account of the stones and turn my face to the pasture to chew. The farmer’s boy doesn’t much come inside the pasture. If he did, I’d try to get up good and close with him. He’s mighty small, compared to Farmer Creely and us cows anyhow. So most times the boy just sets himself up near the fence and plays with dirt and sticks and bugs, like I like to do. When the men and the dogs aren’t around, the boy sings. Sometimes the farmer and the other men catch him singing, and they listen along without him knowing. But other times they tell him to stop his singing and stop bothering us cows. He’s no bother to me or the others from what I can tell, but he won’t sing for days after that. The boy’s got a lot of songs inside. I have songs inside me too, but I reckon I’ll never get a single one of them out speaking as I do. I hear the boy’s song, and I turn. His hair, yellowed as our grass, shades his face from the sun. Alouette, gentille Alouette Alouette—je te plumerai Alouette, gentille Alouette Alouette—je te plumerai Je te plumerai la tête Je te plumerai la tête Et la tête, et la tête Alouette, Alouette O-o-o-o-oh-Alouette, gentille Alouette Alouette—je te plumerai He stops singing. He looks at me with his raindrop eyes and my face heats. “Keep singing.” But he goes silent. I chew and snap my tail. He singsagain, but more quiet now, and I have to stop breathing just to hear him. Je te plumerai le nez Je te plumerai le nez Et le nez, et le nez O-o-o-o-oh-Alouette, gentille Alouette.* That’s the kind of song I’d like to sing I think, and I move my mouth up and back and show my teeth. I dip my head and roll my tongue this way, then that way, then this way again, and show my teeth once more. Other cows are moving past, lots of them, and they see me doing this. This is another horrible day. But the song is with me now; I can hear it just fine inside my cowhead, and walking away from the boy, I sing it best I can. chaptêr two ew cows with craggy brown faces stagger off two big trucks all mussed up, like the dogs have been chasing them in the dark. The chute runs off the trucks are violent and short with cows balking and bucking the whole way down. They make so much racket it blinds me for a while. Some of the new cows collapse as soon as they touch the ground and just lay there, cow folded into cow. But other new cows run angry, especially the bulls, kicking and charging and that makes all us cows angry. “Unnnnnghf, unnnnnnnghf, unnnnnnnghff!” Then it starts like always—bulls charge bulls. Cows charge bulls. Bulls charge cows, and all of us charge calves. With so many cows running around in roaring clouds of hides and horns, I lose my eyes, I lose my ears, and my tongue grows dry and heavy with dust. WhoaCowsWhoaCowsWhoaCowsWhoaCowsWhoaCows! I hear from someplace else. Hoof after hoof mash what little good grasses we got into the dirt, or rip them up from the roots in big patches—and no cow, old or new, got any sense about it. Not even me. I run and charge as a cow too; this way, then that way, then this way again and all over this pasture. I run from fear and I run to fear. The men and dogs shout from the fence, but it doesn’t stop us. For half the day the ground quakes in grotesque shame until all us cows settle. After it all I can hardly move in the center of the cow pack. I strain to lift my head as high as I can. I’m stuck here. We’re all too close, and I stare into the rump of a brown bull whose tail is snapping from side to side. He’s anxious. Flies dart from his dirty haunches to my face, into my eyes, and into my mouth. Bulls should never be this close. I think. I lower my head. I am thirsty but the grass is dry. I close my eyes and let all the air out of my chest. “Unghf.” There’s a lot of comings and goings at Gorwell. A few steer have been here as long as I have but none of them cows stay around for long. The calves come and go about as often. The men just ride their horses in here like thunder on rainstorms, with their dogs rounding us up—calves, cows, and bulls alike. There’s no telling when they’re coming, just a day like any other. You’re chewing grass or just thinking about it, then they got you on the run in all sorts of ways, scrambling about. That’s how it goes. Some of us are dog-chased to the better grasses; others are kept here on grasses already eaten. On occasion, some cows, calves, and a bull or two are chased into the corral where they feed for many days from the farmer’s trough. I don’t know what kind of feed the farmer puts in that trough, but the cows grow big and fat in the corral. And all us other cows, even the ones on good grasses, don’t like them much for doing that—getting fat like they do in plain view of us all. Sometimes I anger so much I’d charge them over and over if I could. But I suppose outside the fences cows got endless green grasses to chew ’cause they never come back here. After some time when they are fattened to the farmer’s liking, the corral cows are herded into that long curved chute by the road, and one by one they walk into that birch-wood building at the far end of the pasture, close to where they bring the sun down. So many gone in that way, I can’t recall a single cow but my mother. Cows aren’t much company anyways, so I don’t really mind all those comings and goings. I surely don’t know what I’d do without that boy, though. He’s been around about as long as me, and longer than most cows on the pasture. He never hears me right, or maybe he just doesn’t want to listen to my cowtalk. I reckon he has nothing to learn from a cow with one good word to say. But I hear him right and good, and by listening to him, the farmer, and some of the farmer’s men, I mostly learn my words. Only the boy knows songs. Cows don’t sing or even talk—least as far as I can tell, but I’m plenty sure they hear ’cause none of us like noise. But I suppose words and songs just don’t go deep enough for the other cows. I pull up close to a milker. She’s eating and guarding some remains of yellowed grass. She’s almost as big as me but chicken white with a speckled peach nose. She’s got swollen udder and one of her teats blown up pink. She stops chewing when I come close, and I stop moving. “Unghf,” I say. Her tail twitches and she lifts her head, then drops it again. I show her my sides. “Unghf,” I say again, flick my ears and move toward her slow. “Anghf,” she says, then goes quiet. I take a few more steps, and I nudge her neck with my nose. “Unghf,” I say, and nudge again. She bends to eat grasses. “Unghf,” I say. But the cow says nothing. I stand and I wait. I lift one front hoof and hold it up. I show her because this is no problem for me. I bend and eat grasses with just my three hoofs to the ground. I chew. “Unghf,” I say dropping my hoof. When the milker looks at me, I turn to her head on to look at her square. Flicking my ears I try to get her to talk with me. “Those men should come soon and move us to the better grass.” Nothing. “I hunger and thirst.” Nothing. “I think they’ll be coming soon.” Nothing. “Do you hear?” And I wait. The milker’s tongue is meaty and coarse, rasping against her snout as she chews cud, grassy juices dribbling from the corners of her mouth. “Unghf,” I say. “You’re a stupid ugly cow.” Nothing. “You dirty the same grasses you eat. You even serve the flies—just like I do.” “Unghf!” I hear, but much louder than my own. I turn. A large black bull is standing behind me. He breathes heavy at me. He lowers his head and shows me his side. His horns are long and sharp, turning inward. He curves his back up and the little hairs along his spine rise. He lifts his head, updown, updown, updown. “Unghf,” he says, “Unghf!” “Unghf,” I say back. I lower my head, draw down my ears, and step back a bit from the milker. I don’t mean trouble, and I reckon she is rightly his cow. “Unghf,” he huffs. “Can you hear me, Black Bull?” He lowers his head and digs at the soil with his front hoof. “Do you even know what you are?” Nothing. “Your life is a curse.” Nothing. “You just have no mind about it.” He charges me. “être!” I say, and I run. “Listen to me! Listen to me, listen to me! Cows hear me!” But with those words locked in my cow body, I cannot stir them, and I shout the only word I got, my name. “Coohoo, coohoo, coohoo,” the chickens say, but there’s no sense to any of it. I poke my head out of the pasture through the fence wires close to the chicken pen, and they scatter, flapping their wings wildly. The top wire rips into my ear as it always does, and I will tear the other ear when I pull myself back inside. I know this much. Such desires pain us cows, but the grass on the strip between the pasture and the pen is green and long and delicious with no other cows chewing on it or otherwise disgracing it. Even the air out on the strip has only a hint of cow, and I breathe it in large gulps. When the pain in my ear subsides, I dig my face into the grass and pull the thick blades out of the soil. The chickens pitch themselves up and down, sending white feathers into the air. “Coohoo! Coohoo!” they warn. Can’t talk sense to them chickens, it’s no use. Only chickens are more lowly than us cows, walking on two legs like men but cursed with wings that will never fly. “Coohoo, coohoo!” the chickens scream. “Unghf,” I say, and I chew. “Owf! Owf! Owf!” a filthy dirt-colored dog darts over, snarling and barking at my massive grass-poaching cowhead, and sending the chickens into more flapping foolishness. “Coohoo! Coohoo!” “OwfOwfOwfOwfOwfOwfOwfOwfOwf!” Dogs have sharp teeth, and I’ve known a few to use them. I try to pull back, but my head is caught. “Coohoo! Coohoo!” “Unghf,” I say to the dog, but he keeps barking at me, bouncing on his front paws with his hind in the air. “Whiiirp!” the farmer whistles. “Get along now Rexy and leave the cow be!” “OwfOwfOwfOwfOwfOwfOwfOwfOwf!” “Unghf.” “Coohoo! Coohoo!” “OwfOwfOwfOwfOwf!” “Rexy!” the farmer shouts. “Owf! Owf” “C’mon, Boy! C’meer, Rexy,” the boy says. “Owf! Owf!” The farmer whistles again, the dog leaves me be, and I chew good grass. The farmer stops so close to me he blocks the sun, and his boy follows. I try to pay them no mind, and I move the cud around my mouth and I swallow. “A fine mess you’re in here, cow.” “I think his head is stuck,” the boy says. “Yeah, I reckon it is,” the farmer says. “Well let’s let him be. He figured how to get his head through the fence, he’ll figure how to get his head back in.” “You think?” “’Spose he will.” The boy begins to laugh. This is the very best sound the boy makes, and I stop chewing to watch him. “You seeing something funny here, Jacques?” “He looks so,” the boy snorts, “he looks so, he looks so . . . stupid,” and then explodes in laughter. “Unghf,” I say, which makes the boy laugh even harder. “Shush now, Jacques, shush yerself! You don’t want to spook him with a head stuck like that. He’ll likely hurt himself or end up pulling the whole side of fence down.” “Sorry, Paw! It’s just, it’s just, it . . . ” “Shush now. Cows don’t know right from wrong, up from down, shit from sunshine. But this one here looks rightly smart. He’s trying to get at the good grass here, see? None of them other cows figuring that sorta thing out, now are they?” “’Spose no.” “’Spose no is right, boy, and besides, cows ain’t so dumb as people think. They get along best they know how, just like you and me. They know cowin’, we know farmin’, bugs know buggin’. And that’s how it goes. Come on now, leave him be.” “But what if he’s really stuck?” “And what if he is?” “Won’t he choke and die?” “Reckon he might, but that don’t change much, we got lots of cows. Besides, he’ll die happy eating all that good grass. C’mon, Jacques, he’ll be fine, leave him, we got work waitin’,” the farmer says, walking away. “Jacques?” The boy moves closer to my head and reaches slowly for the top wire. I lift my head to feel him and he recoils, knotting his tiny hands together against his chest. “Jacques? I said the cow’ll be fine. Leave him be.” “But, Paw, what if he can’t . . . ” “He can, son. He can, and he will.” The boy still won’t leave me, so the farmer comes back, moving him aside. “Okay, cow, back where you belong,” the farmer says, lifting the wire over my horns. He cups my wounded ear with his other hand; it is hard like wood, and he pushes my cowhead back where it belongs. I look out at them from inside the pasture. “Don’t he look sadder to you now, son?” the farmer says. “Reckon he does.” “I reckon he does too. Leave him be, let’s go now.” “Coohoo, coohoo, coohoo,” the chickens say. “’K, Paw.” “’K now, let’s move on,” the farmer says, and with the dog grinning between his legs, they walk off.Discussion Questions

1. In French the verb "etre" means "to be" or "to exist". In the novel, "etre" is the name of the protaganist cow, but also the only word he can say aloud. Discuss the implications of this. Is Etre struggling for existence, undertanding, significance, or all three?2. Etre the Cow is an allegory, in the tradition of George Orwell's classic 1945 novella Animal Farm. While Animal Farm serves as an indictment of totalitarian regimes, Etre the Cow uses allegory to critique contemporary society. Written during the recession of 2008 and 2009, discuss the social, political and economic context that Etre the Cow is responding to.

Notes From the Author to the Bookclub

The central theme of ETRE THE COW is a struggle for self-determination and freedom. In the story, Etre is powerless over nearly every aspect of his life. When my position was eliminated from a major U.S. corporation I felt like I had been a naïve cow. My termination made me feel powerless and humiliated. With the economy, job loss, housing crisis millions of Americans feel the same. When did we lose so much power over our own lives? About the book as a bookclub book - What makes this such a wonderful bookclub book -what other clubs have said. * Since everyone who reads Etre the Cow gets something different out of the existential parable, it automatically makes it an excellent topic of conversation for book clubs. * Everyone who's read the book has much to say about it. Never a simple "I liked it", "it was great" or they didn't. There will be no shortage of commentary on this book, especially in a club setting. If readers dissect the symbolism in the book, they will see parallels between today's world and Etre's pasture. The book not only tells you what it is like to be a cow, but by extension, what it is to be human. Author Q&A 1. What was your inspiration for writing ETRE THE COW? During the recession of 2008 and 2009 millions of Americans lost their jobs, their homes, their life-savings, and their self-worth. I was one of them. I too became a victim of the economic downturn when my position at a major U.S. corporation was suddenly eliminated. I felt tossed aside, discarded and abandoned. As I drove home with my termination papers in the passenger seat of my Jeep I passed the cow pasture at the end of my block. I had passed this cow pasture every day on my way to work, but never really looked at the cows. I stopped and looked into their sad cow faces, and that's when I realized we share a common story. I went to live with the cows-I studied them, I communed with them. 2. Had you had any experience with livestock before? No. I am from New York. I am a doctor and did my medical training in NY City. I still do not have a lot of experience with cows. Cows are dangerous animals. Depending on the breed, mature cows can weigh anywhere from a few hundred pounds to two-thousand. According to the CDC roughly 20 people are killed each year by cows. Hundreds more are injured. Cows can be aggressive and they have been known to attack people without provocation-especially dams (mother cows) and bulls. So I studied cows, but from a safe distance. I watched how they interacted with each other and how they interacted with people. 3. What did you learn about cows? Cows are much more intelligent animals than most people realize. They are emotional creatures and in some cases they are disturbingly rational. There have been many instances where cows have escaped imminent slaughter or attempted to escape it. Cows are also very humble creatures. If you look closely enough, some of them are aware of their own indignity. I suspect some cows realize they are fenced in, powerless, and occupying one of the lowest links of the food chain. You can see it in their eyes. 4. Are you a vegetarian? No. But I do prefer to eat chicken and fish-for general health reasons and now for moral reasons. After writing this book it has become increasingly difficult for me to eat beef. Many people who have read ETRE THE COW have stopped eating beef altogether. Now I have a fuller understanding of why people decide to be meatless. 5. The most notable author to utilize animal allegory as a form of social criticism is George Orwell. His classic 1945 novella, ANIMAL FARM, served as a critical indictment of totalitarian governments. How does ETRE THE COW compare to ANIMAL FARM, and what aspects of contemporary society is ETRE THE COW criticizing? Other than the allegorical form and the pastoral setting there are few parallels between ETRE THE COW and ANIMAL FARM. In fact there is a critical difference between the two books. In Orwell's ANIMAL FARM three power hungry pigs compete for absolute power. In ETRE THE COW there is a complete lack of power. Etre is utterly powerless. Depicting this powerlessness is the social critique. In Etre's world and ours the impotence is so thick it binds. With millions of lost jobs, lost homes, and lost savings-haven't many ordinary people lost a substantial amount of power over their very own existence? We are all fenced in and powerless to some extent. 6. The verb "etre" means "to be" or "to exist" in French. The Farmer's boy, Jacques, sings lullabies in French. Is there a reason why you choose French? Yes. The main crisis in ETRE THE COW is an existential one. Etre is fighting for his life in a literal sense, but in a figurative sense he is struggling for significance, for recognition, for existence. What does his cow life mean? And who gets to decide what his life means? Since the French have a long tradition of existential literature, like the writings of Jean-Paul Sartre and Albert Camus, the language seemed natural. Plus I speak a little French. The French lullabies in ETRE THE COW, like Frère Jacques and Alouette-Alouette, are recognized by most native English speakers-but few know the meaning of the words. So I wanted to create a setting that was familiar, but unfamiliar. On the surface Etre's world seems very different from our own, but on a deeper level our worlds are very similar. 7. This is not a children's book. There is a brutal slaughter scene, and Etre kills the Farmer's boy. He deliberately crushes the boy under his hooves. Why does Etre kill Jacques? Etre loves Jacques, and in the simplest sense Etre hopes to stop the processing of cows by killing the boy. Sometimes we have to kill the things we love in order to live. But also in a metaphorical sense, the boy represents naïvete-more specifically he represents Etre's naïvete. After Etre witnesses the carnage inside the slaughterhouse Etre's world unravels. He has many revelations about his life and about the world. So Etre's naïvete dies. So by killing the boy, Etre is actually killing his own naïvete. 8. The cows don't say "moo" in ETRE THE COW. Why? If you have ever heard the sound cows actually make, it sounds nothing like "moo." So I wanted to create the "familiar, yet unfamiliar" sound cows make by using a more phonetic "unghf" and "anghf." Interestingly, these sound very similar to a human groan. Cows "mooing" sound a lot like very frustrated people. It's as if cows have something to say, but it is bottled up in their cow bodies. I tried to create that sensation. 9. What do you hope readers will learn from reading ETRE THE COW? The book has meant different things to different people, so I think the discoveries will be individualized. However, I do hope the central message of ETRE THE COW will resonate with most readers. We are all cows in a sense. We are all defined by the fences that surround us, and the pastures we graze on. But it doesn't have to be that way. You can break down your fences and seek greener pastures. You can challenge fate. You can change your destiny. Push your limits and define your own life. 10. You were part of the original cast of the hit CBS reality show Survivor. The show is now celebrating its tenth year. Did your experiences on Survivor help you in writing ETRE THE COW? Yes. Especially the humiliating parts of it.Book Club Recommendations

Recommended to book clubs by 0 of 0 members.

Book Club HQ to over 90,000+ book clubs and ready to welcome yours.

Get free weekly updates on top club picks, book giveaways, author events and more